A gene editing tool using a system known as CRISPR-Cas9 has recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for sickle cell disease. The drug is known as Casgevy and the media has hailed this treatment as a ‘cure’ for sickle cell anemia patients. While it is still unclear if the drug completely cures these patients, clinical trials show exciting efficacy.

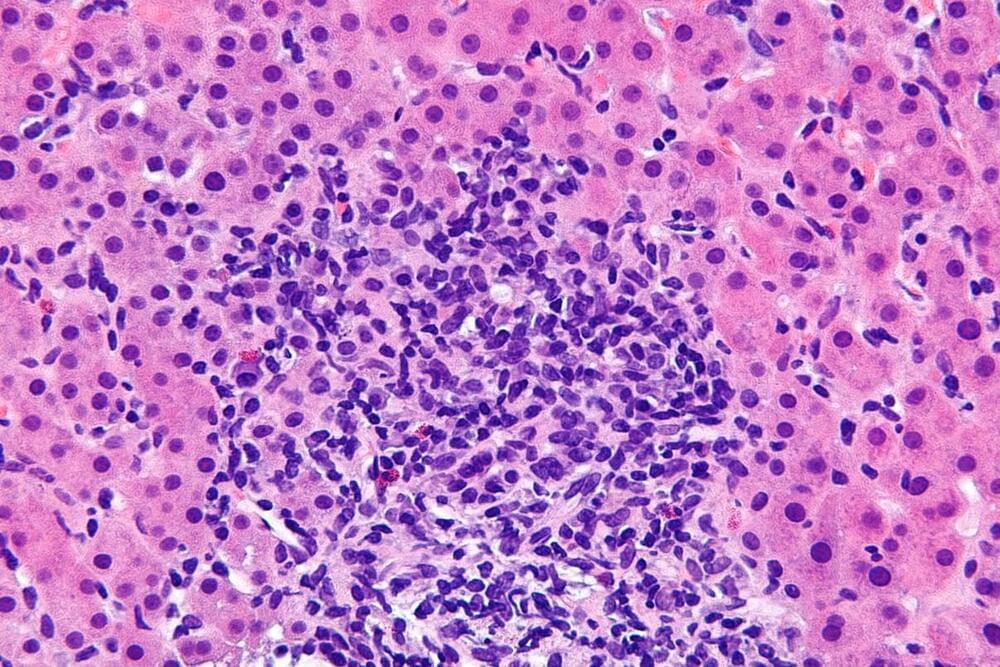

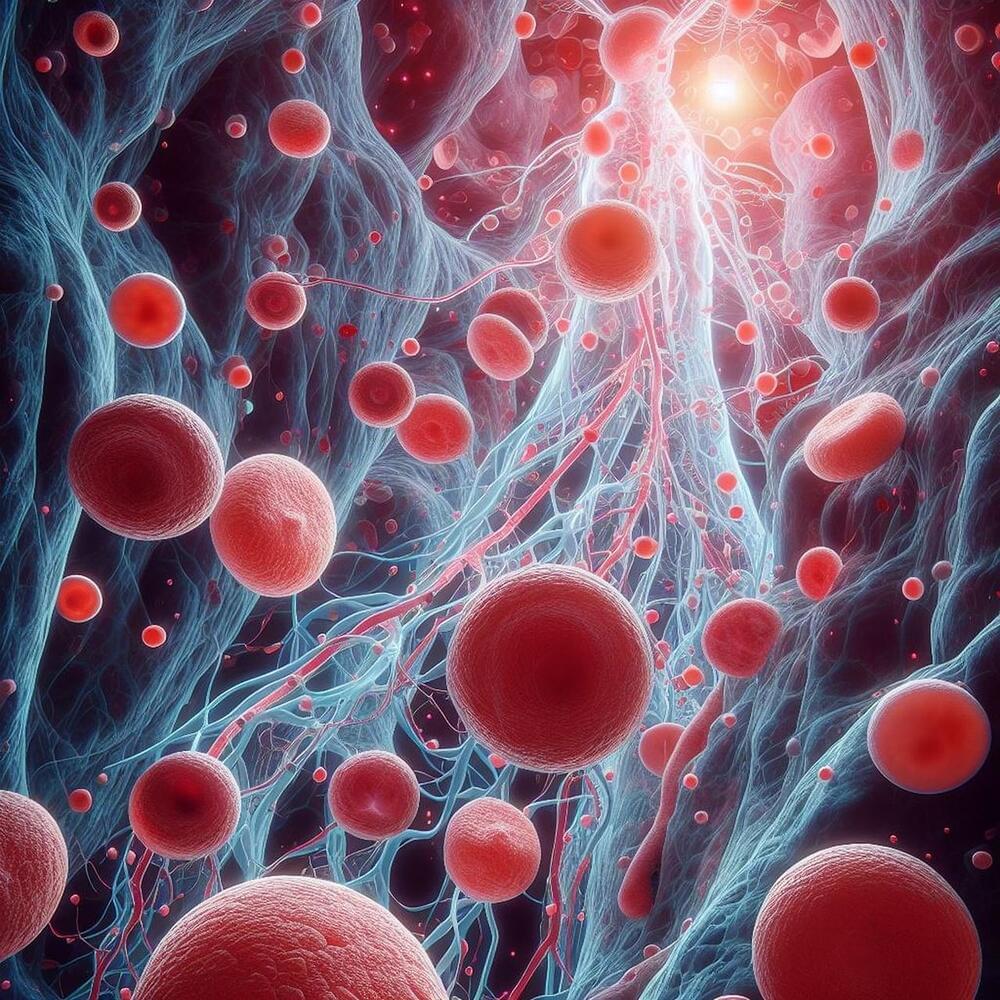

Sickle cell disease is a genetic blood disorder affecting thousands of US citizens. Many of these patients are African American and Hispanic. In sickle cell disease, hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that helps carry oxygen throughout the body, is mutated. As a result, blood cells change shape in the form of a sickle, giving the disease its name. Unfortunately, the mutated cells cause disruption of blood flow and prevent other blood cells from delivering oxygen to the body. This disease is extremely rare and can lower the quality of life in patients. Previously, there were limited treatments options including transfusions and medications for pain management. However, Casgevy provides a new option to help treat the patient and relieve pain for over a year after a single treatment.

One-time treatment using Casgevy improved life quality for sickle cell patients. A single-arm trial was conducted at multiple health centers in adults and adolescents. These patients were screened for two vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) which are described as severely painful events due to a lack of oxygen delivery from sickle cell blood cells blocking blood flow. The primary measure of success in the trial was the number of VOCs after treatment. In total, 44 patients received Casgevy and 33 were able to follow up and be evaluated. Of the 33 patients that made it through the trial, 29 of them did not experience any VOCs for 12 months. This is a 93.5% success rate based on the number of patients that were analyzed. All 44 patients were able to successfully undergo treatment without any graft rejection. In addition, researchers concluded that this treatment was not only effective, but safe with few side effects.