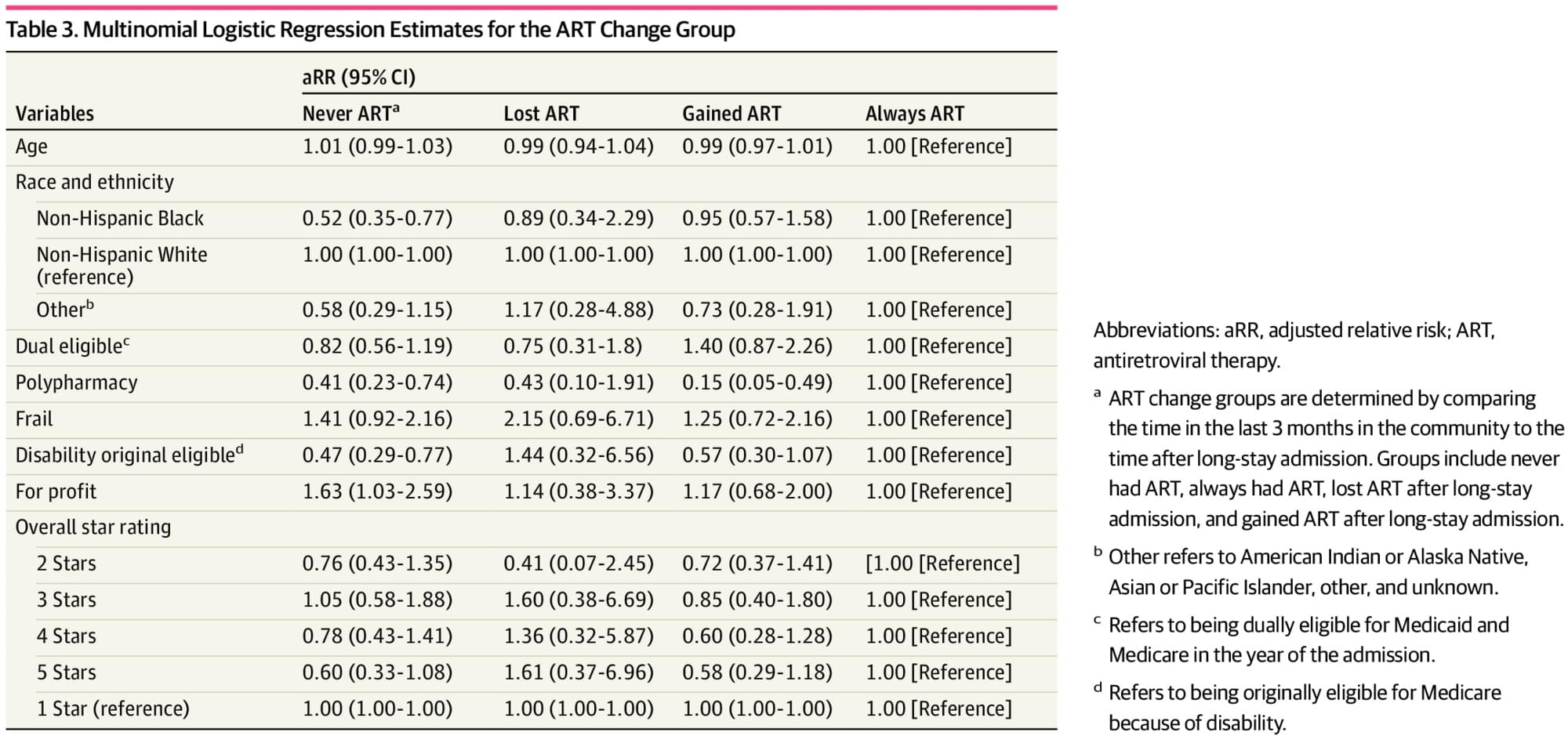

Access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) appears to improve when Medicare beneficiaries with HIV transition to long-term nursing homes, but nursing homes miss opportunities for initiation, as most stays without ART never had ART before admission.

This cohort study aimed to understand changes in ART use for Medicare beneficiaries with HIV transitioning from the community to long NH stays. We found that among a group with a mean age of 61 years, ART use seemed to improve after the transition, that there was no ART use before or after the transition for nearly one-quarter of our sample, and that comorbidities and frailty had no association with ART changes. These findings are contrary to our hypothesis that posited lower ART use after the transition and that lower NH quality rating would be associated with even lower ART use. These findings are critically important to our understanding of NH care for people with HIV because they dispel select concerns that the transition to long-stay NH resident and the transition from Medicare Part A to Part D medication benefits are opportunities for reduced ART use.

Few NHs have experience caring for people with HIV, with many seeing only 1 or 2 individuals in a 3-year span.9 Experience with HIV care correlates with better health outcomes in both the NH setting and the outpatient setting.8 Many community-based studies have found that better adherence to ART is associated with older age,29, 30 and 1 study of NH residents with HIV showed that longer duration of an NH stay was associated with better ART adherence,13 although that same study found that 21% of people with HIV in NHs had no ART. Without following people from the outpatient or community setting into the NH setting, these previous studies were limited in their generalizability because of selection bias; they examined only people with HIV using outpatient services, or only people with HIV using NHs.