The motions within the molecule provide a new way to compare the structures and functions of similar proteins.

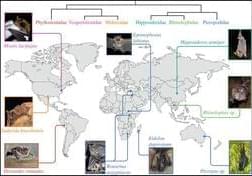

Proteins play a central role in nearly every biological process, and they often change shape as they function. Over the past decade, a research team has developed a method of analysis that can help make sense of the available atomic-scale structural data and reveal the key physical distortions that underlie protein functions. Now the team has shown that the technique provides a consistent way of comparing proteins from different species, demonstrating similar structural changes in many of them [1]. The researchers believe that the technique will help biologists better understand the cross-species variations among proteins.

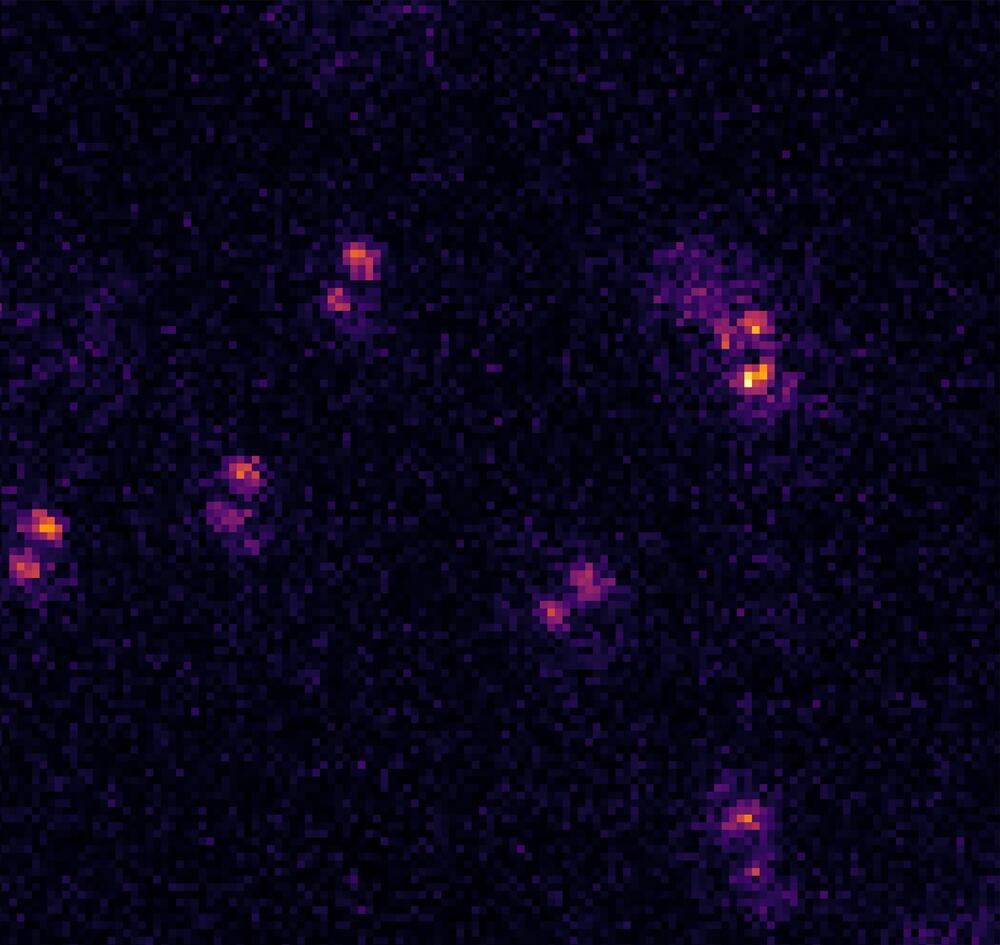

Proteins are linear chains of amino acids that fold up into specific three-dimensional shapes. Although there are lots of atomic-scale data on the structural changes that protein molecules execute as they function, researchers have had few quantitative methods to extract insights from these data, says biophysicist Pablo Sartori of the Gulbenkian Institute of Science in Portugal. One challenge, he says, is the arbitrary choice one makes when comparing two similar protein structures, such as the structures of a protein in two different conformations. “If you align region A of the protein, then region B shows displacement. If you align region B, then region A shows displacement. If you align the average, then both are displaced a bit.” Another problem is that the relative displacement is often not the quantity that best reflects the structural changes associated with protein function.