But they don’t. Instead, they are less likely to develop or die of this enigmatic disease. The same is true of elephants and dinosaurs’ living relatives, birds. Marc Tollis, an assistant professor in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems at Northern Arizona University, wants to know why.

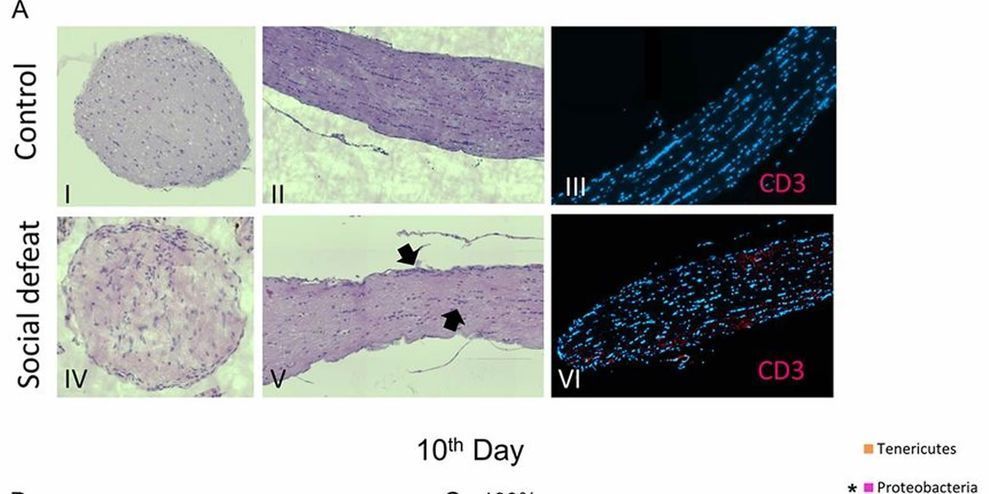

Tollis led a team of scientists from Arizona State University, the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, the Center for Coastal Studies in Massachusetts and nine other institutions worldwide to study potential cancer suppression mechanisms in cetaceans, the mammalian group that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Their findings, which picked apart the genome of the humpback whale, as well as the genomes of nine other cetaceans, in order to determine how their cancer defenses are so effective, were published today in Molecular Biology and Evolution.

The study is the first major contribution from the newly formed Arizona Cancer and Evolution Center or ACE, directed by Carlo Maley under an $8.5 million award from the National Cancer Institute. Maley, an evolutionary biologist, is a researcher at ASU’s Biodesign Virginia G. Piper Center for Personalized Diagnostics and professor in the School of Life Sciences. He is a senior co-author of the new study.