Magnetically controlled device could deliver clot-reducing therapies in response to stroke or other brain blockages.

Category: biotech/medical – Page 2,732

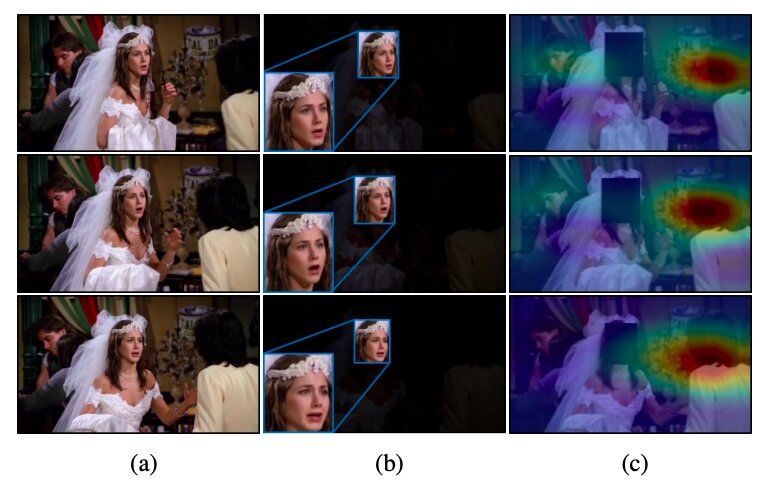

A deep learning technique for context-aware emotion recognition

A team of researchers at Yonsei University and École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) has recently developed a new technique that can recognize emotions by analyzing people’s faces in images along with contextual features. They presented and outlined their deep learning-based architecture, called CAER-Net, in a paper pre-published on arXiv.

For several years, researchers worldwide have been trying to develop tools for automatically detecting human emotions by analyzing images, videos or audio clips. These tools could have numerous applications, for instance, improving robot-human interactions or helping doctors to identify signs of mental or neural disorders (e.g.„ based on atypical speech patterns, facial features, etc.).

So far, the majority of techniques for recognizing emotions in images have been based on the analysis of people’s facial expressions, essentially assuming that these expressions best convey humans’ emotional responses. As a result, most datasets for training and evaluating emotion recognition tools (e.g., the AFEW and FER2013 datasets) only contain cropped images of human faces.

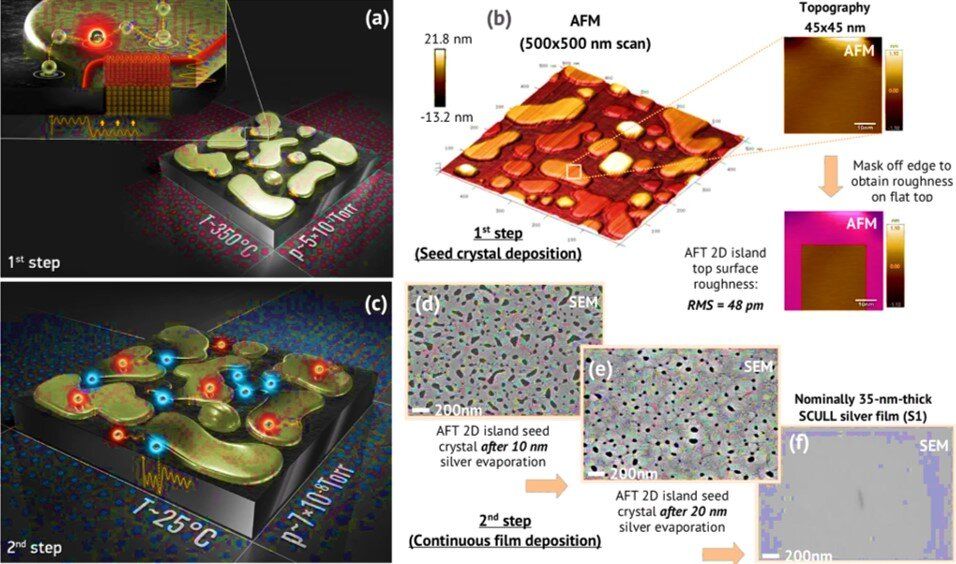

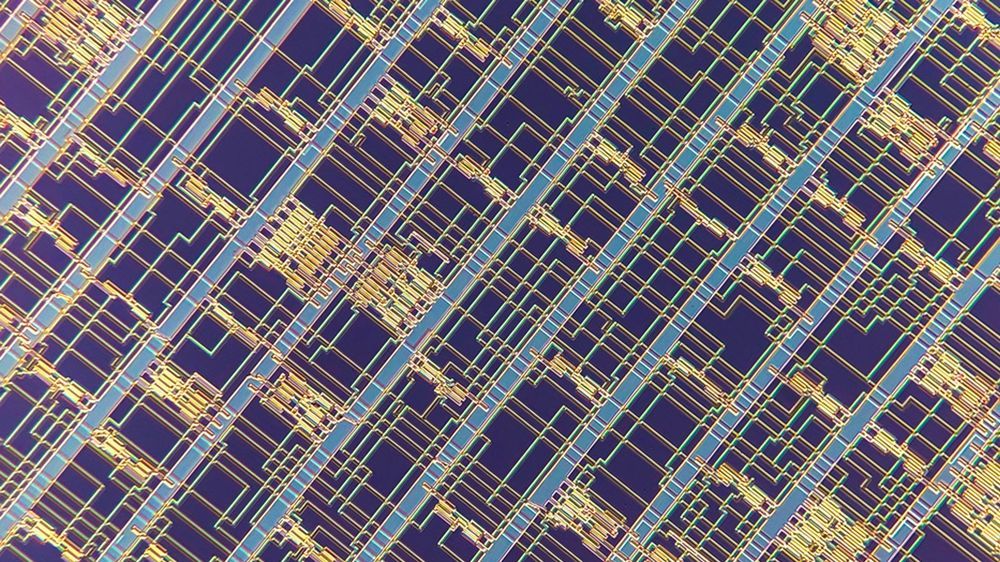

Quantum engineering atomically smooth single-crystalline silver films

Ultra-low-loss metal films with high-quality single crystals are in demand as the perfect surface for nanophotonics and quantum information processing applications. Silver is by far the most preferred material due to low-loss at optical and near infrared (near-IR) frequencies. In a recent study now published on Scientific Reports, Ilya A. Rodionov and an interdisciplinary research team in Germany and Russia reported a two-step approach for electronic beam evaporation of atomically smooth single crystalline metal films. They proposed a method to establish thermodynamic control of the film growth kinetics at the atomic level in order to deposit state-of-the-art metal films.

The researchers deposited 35 to 100 nm thick, single-crystalline silver films with sub-100 picometer (pm) surface roughness with theoretically limited optical losses to form ultrahigh-Q nanophotonic devices. They experimentally estimated the contribution of material purity, material grain boundaries, surface roughness and crystallinity to the optical properties of metal films. The team demonstrated a fundamental two-step approach for single-crystalline growth of silver, gold and aluminum films to open new possibilities in nanophotonics, biotechnology and superconductive quantum technologies. The research team intends to adopt the method to synthesize other extremely low-loss single-crystalline metal films.

Optoelectronic devices with plasmonic effects for near-field manipulation, amplification and sub-wavelength integration can open new frontiers in nanophotonics, quantum optics and in quantum information. Yet, the ohmic losses associated in metals are a considerable challenge to develop a variety of useful plasmonic devices. Materials scientists have devoted research efforts to clarify the influence of metal film properties to develop high performance material platforms. Single-crystalline platforms and nanoscale structural alterations can prevent this problem by eliminating material-induced scattering losses. While silver is one of the best known plasmonic metals at optical and near-IR frequencies, the metal can be challenging for single-crystalline film growth.

End of fillings in sight as scientists grow tooth enamel and repair damage

The end of fillings could be on the horizon after scientists found a way to successfully grow back tooth enamel. Although many laboratories have attempted to recreate the outer protective layer of teeth, the complex structure of overlapping microscopic rods has proved elusive.

Tooth enamel is the hardest tissue in the human body but it cannot repair itself when damaged, leaving people exposed to cavities and eventually needing fillings or a tooth extraction.

Experimental drug may ease opioid withdrawal symptoms

Opioid withdrawal is a challenging experience, and although there are medications already on the market that can help curb the symptoms of withdrawal, these drugs cause negative side effects.

Current withdrawal medications also often require people to take them for a prolonged period, which is not ideal and could lead to a relapse.

There may be encouraging news on the horizon, however. New research highlights the possible benefits of an experimental drug called rapastinel, which scientists initially created to help those with major depressive disorder.

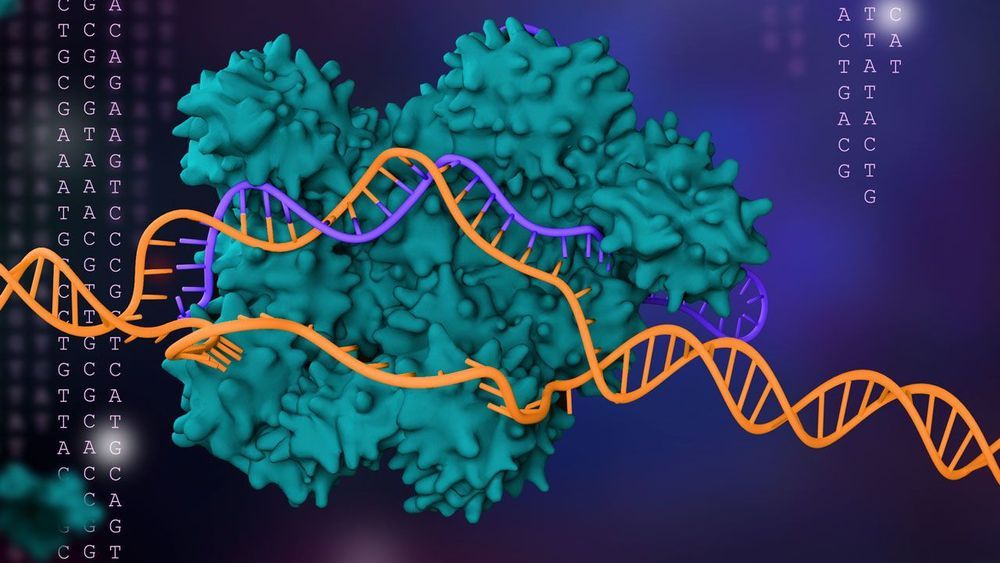

WATCH: This two-minute synthetic biology video is a far-out vision of the future

Most of my professional life is centered on synthetic biology, an industry and movement to make biology easier to engineer. So far, this emerging discipline has yielded everything from living medicines and spider silk jackets to impossible hamburgers. But what will humankind be growing in the next century?

Rejuvenation biotechnology: Will “age” soon cease to mean “aging”?

Around the world, people are living longer — not just because child mortality is dropping, but also because we’re staying healthy for more years as we age. In the future, regenerative medicine and other new developments may help most people remain youthful much longer than they do today. In this talk, Aubrey de Grey, Chief Science Officer at the SENS Research Foundation, discusses the biology and sociology of what could be a massive shift in the way we live.

To learn more about effective altruism, visit effectivealtruism.org

This talk was filmed at EA Global 2019: San Francisco. You can learn more about these conferences at eaglobal.org