Two different marketplaces for genetic data, Nebula and EncrypGen, recently launched with the promise of better protections for their users.

Chemical substances and nanomaterials are processed on a massive scale in diverse products, while their risks have not been properly assessed. Time and again synthesised substances have been shown to pollute the environment more than lab tests predicted. This is the warning given by Professor of Ecotoxicology Martina Vijver from Leiden University in her inaugural lecture on 16 November.

Laboratory tests are inadequate, according to Vijver, because they do not imitate a complete ecosystem. In her inaugural lecture she will discuss in greater detail two examples of substances where more realistic research is needed: agricultural toxins and nanoparticles. ‘But the same can be said for many other groups of substances, such as antibiotics, plasticizers and GenX.’

Tell the FDA to identify and punish organisations who have broken US law by not reporting clinical trial results.

The US’s Food and Drug Administration has at last published its plan to identify and punish the organisations and people who have broken the law by not reporting clinical trial results. The FDA now wants to hear what we think about the plan.

The FDA Amendment Act 2007 says that lots of clinical trials in the US should be registered on ClinicalTrials.gov and report results information there within 12 months of the end of the trial. AllTrials’s FDAAA TrialsTracker shows that 628 clinical trials have broken this law since the first trials became due in January this year. We have written to the FDA every week to update them on the trials that have breached the law and shared with them a rolling estimation of the amount in fines the Agency could levy on the law breakers. The FDA has the power to fine people up to $10,000 a day and we have assessed that they could have raised $904,499,127 – nearly a billion dollars – but no one has ever been fined. That the FDA is now seriously considering how to start doing this is a long-awaited step forward.

These are the draft guidelines. The FDA is asking for comments on them to be submitted here. You don’t have to be a US citizen to comment.

Thoughts on the Eurosymposium on Healthy Ageing held by Heales in Brussels.

When I first learned about the possibility of achieving human rejuvenation through biotechnological means, little did I know that this would lead me to meet many of the central figures in the field during a conference some seven years later—let alone that I would be speaking at the very same event. Yet, I’ve had the privilege to attend the Fourth Eurosymposium on Healthy Ageing (EHA) held in Brussels on November 8–10, an experience that gave me a feel of just how real the prospect of human rejuvenation is.

A friendly, welcoming environment

As EHA was the first conference I’ve ever attended, I didn’t quite know what to expect; given that researchers, activists, and investors from all around the world were invited, I had imagined it would probably be a posh, formal event with violins playing on the background and people in suits and formal dresses discussing topics beyond my comprehension while enjoying champagne. Thankfully, the atmosphere was much more relaxed and informal, elegant but not intimidating, which favored the interaction among participants regardless of their backgrounds—though, alas, the topics discussed were indeed mostly beyond my comprehension, as they involved high-level biochemistry with which I’m nowhere near sufficiently familiar (yet).

LEXINGTON, Ky. (NOVEMBER 15, 2018) – Space Tango, a leader in the commercialization of space through R&D, bioengineering and manufacturing in microgravity, today announced ST-42, a fully autonomous robotic orbital platform designed specifically for scalable manufacturing in space. Launching in the mid 2020’s, ST-42 aims to harness the unique environment of microgravity to produce high value products across industries; from patient therapeutics to advanced technology products that have the potential to revolutionize industries here on Earth. ST-42 is an extension of the International Space Station’s (ISS) capabilities, and NASA’s creation of a robust commercial marketplace in low Earth orbit (LEO).

ST-42 will bring the economics of production in orbit into reality coupling autonomy with the reduced cost and larger number of launch vehicle providers. Space Tango expects the platform to be at the forefront of new breakthroughs in knowledge discovery, therapeutic solutions and manufacturing, and to provide the required capabilities for creation of new biomedical and technology product sectors in the commercial Space economy.

A new study takes a look at the relationship between metabolism, aging, and type 2 diabetes and in particular the mTORC1 protein complex, part of the mTOR pathway.

The mTOR pathway

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a major part of metabolism and is one of four major pathways that control it; collectively, the four pathways are part of deregulated nutrient sensing, which is one of the aging processes.

Research led by the University of Bristol has begun to unpick an important mechanism of antibiotic resistance and suggest approaches to block this resistance.

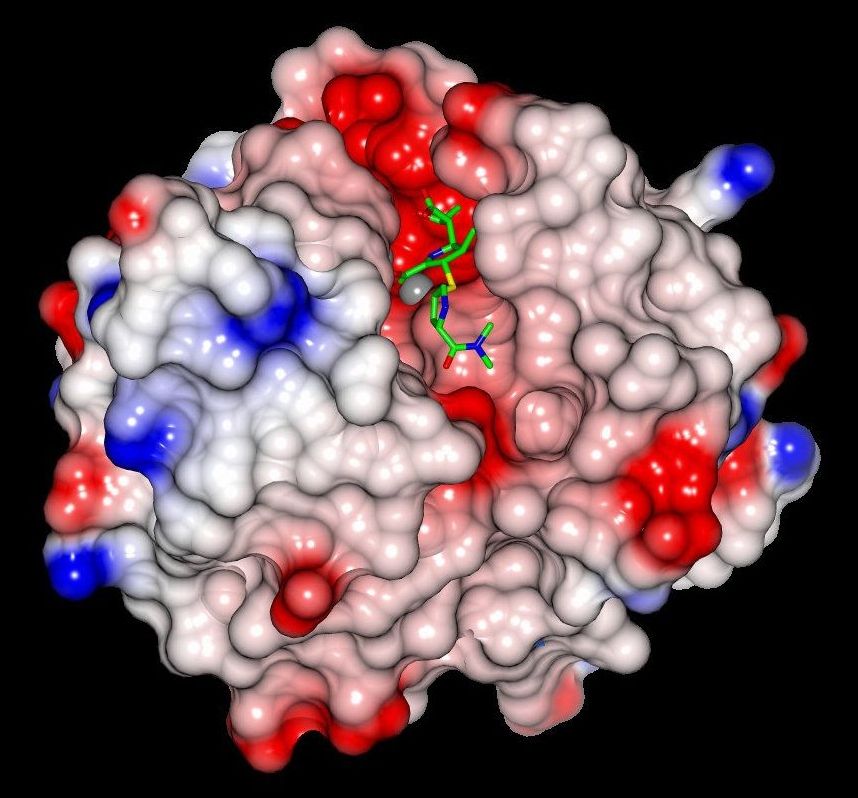

Antibiotic resistance is the ability of bacteria to defend against antibiotic attack, and the spread of these resistance mechanisms amongst bacteria is a global public health concern. A form of resistance caused by a family of bacterial proteins, the Verona Imipenemase (VIM) beta-lactamases, is of acute clinical concern because it can inactivate antibiotics (penicillins and related agents) that comprise over half of the global antibacterial market.

A team of researchers led by the University of Bristol have uncovered near-atomic level structural detail of VIM proteins. The research is published today [Thursday 15 November] in The FEBS Journal.

A man in his 50s is the first of seven patients to receive the experimental therapy.

Practices to enable more-thorough, earlier analyses of failed developments should be adapted to treatments for other challenging diseases, and should be part of regulators’ responsibilities. This will ensure that clinical research evaluates treatments faster and with more certainty.

Access to evidence from disappointing drug-development programmes advances the whole scientific process, explain Enrica Alteri and Lorenzo Guizzaro.