“In quantum many-body theory, we are often faced with the situation that we can perform calculations using a simple approximate interaction, but realistic high-fidelity interactions cause severe computational problems,” says Dean Lee, Professor of Physics from the Facility for Rare Istope Beams and Department of Physics and Astronomy (FRIB) at Michigan State University and head of the Department of Theoretical Nuclear Sciences.

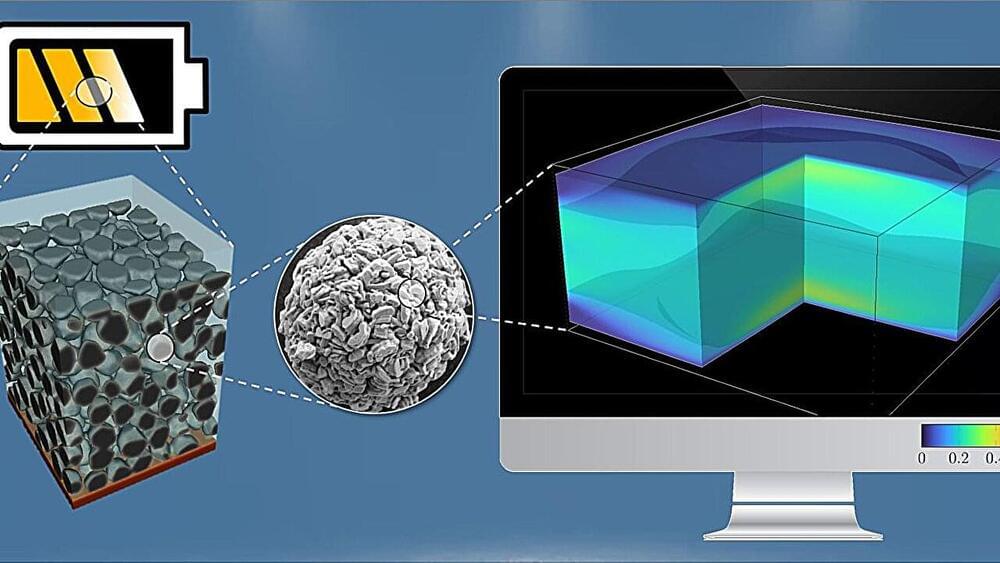

Practical Applications and Future Prospects

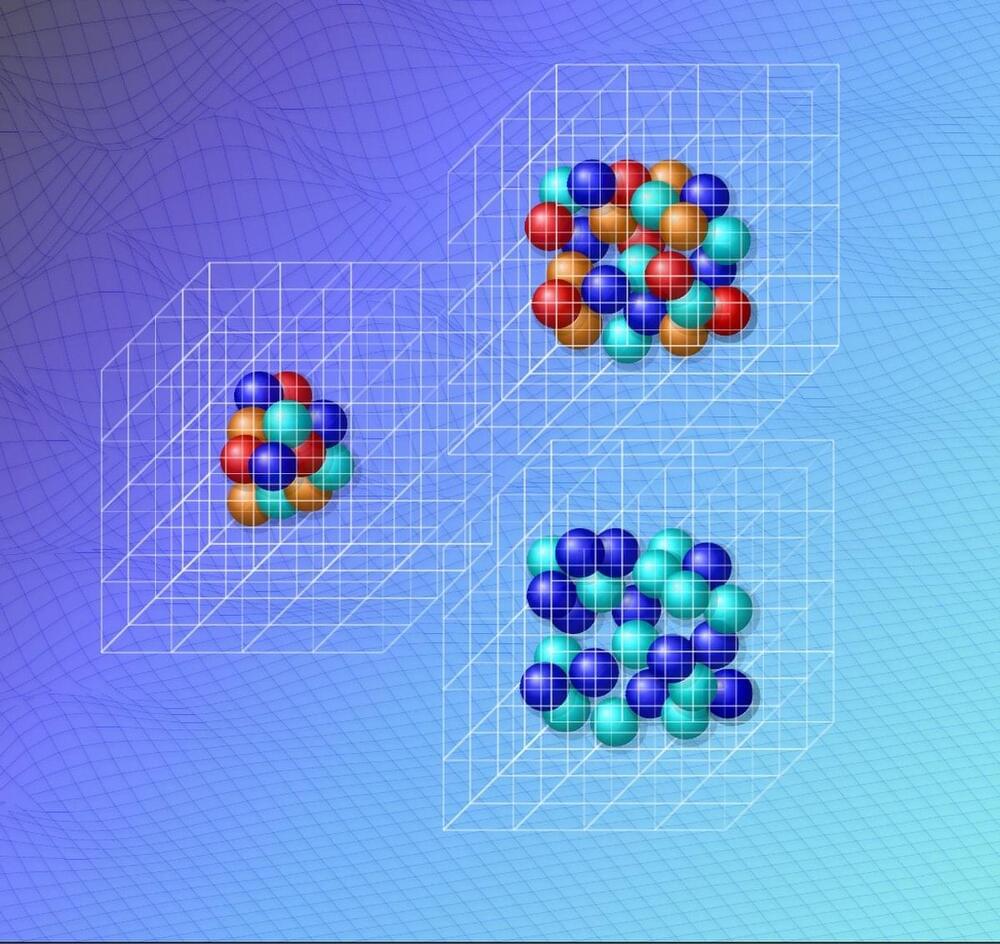

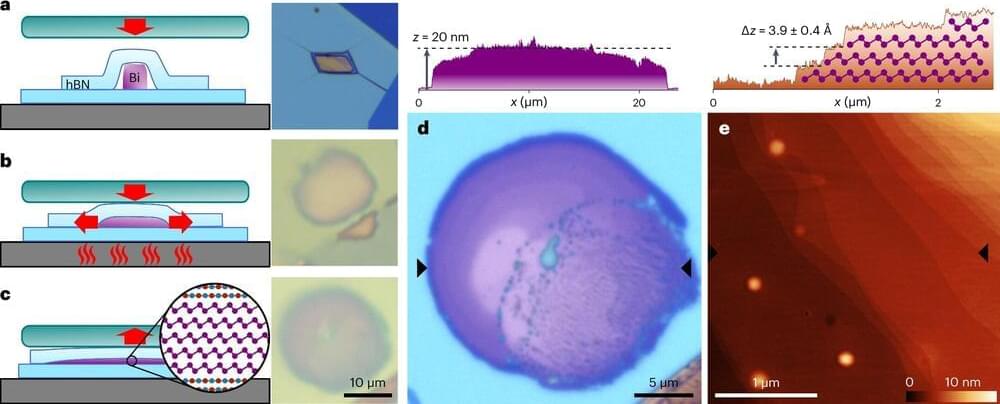

Wavefunction matching solves this problem by removing the short-distance part of the high-fidelity interaction and replacing it with the short-distance part of an easily calculable interaction. This transformation is done in a way that preserves all the important properties of the original realistic interaction. Since the new wavefunctions are similar to those of the easily computable interaction, the researchers can now perform calculations with the easily computable interaction and apply a standard procedure for handling small corrections – called perturbation theory.