Beijing is pushing a ‘whole-of-the-nation’ approach to focus resources on tech breakthroughs in key areas amid rising pressure from the US.

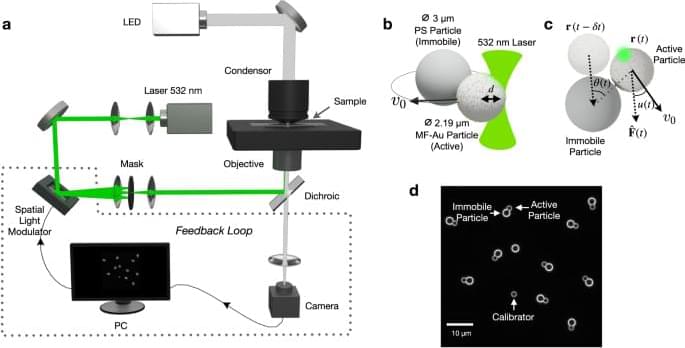

The ability of living systems to process signals and information is of vital importance. Inspired by nature, Wang and Cichos show an experimental realization of a physical reservoir computer using self-propelled active microparticles to predict chaotic time series such as the Mackey–Glass and Lorenz series.

Ok… here we go again! (Yes, this is real. Already being tested in full wafers.)

To try everything Brilliant has to offer—free—for a full 30 days, visit https://brilliant.org/Inkbox. The first 200 of you will get 20% off Brilliant’s annual premium subscription.

I designed my own 16-Bit Computer in Microsoft Excel without using Visual Basic scripts, plugins, or anything other than plain Excel. This system on a spreadsheet is based off of a custom Instruction Set Architecture that has a total of 23 instruction mnemonics and 26 opcodes.

The main design of the CPU is broken into a fetch unit, control unit, arithmetic logic unit, register file, PC unit, several multiplexers, a memory control unit, a 128KB RAM table, and a 128×128 16-color display.

Try it out down below:

https://github.com/InkboxSoftware/excelCPU

This video was sponsored by Brilliant.

computer chip by MITHUN T M from Noun Project.

Memory by Alvida from Noun project.

Calculator by Uswa KDT from Noun Project.

With a quick pulse of light, researchers can now find and erase errors in real time.

Researchers have developed a method that can reveal the location of errors in quantum computers, making them up to ten times easier to correct. This will significantly accelerate progress towards large-scale quantum computers capable of tackling the world’s most challenging computational problems, the researchers said.

Led by Princeton University ’s Jeff Thompson, the team demonstrated a way to identify when errors occur in quantum computers more easily than ever before. This is a new direction for research into quantum computing hardware, which more often seeks to simply lower the probability of an error occurring in the first place.

Jan 29 (Reuters) — The first human patient has received an implant from brain-chip startup Neuralink on Sunday and is recovering well, the company’s billionaire founder Elon Musk said.

“Initial results show promising neuron spike detection,” Musk said in a post on the social media platform X on Monday.

Spikes are activity by neurons, which the National Institute of Health describes as cells that use electrical and chemical signals to send information around the brain and to the body.

“Not every planet is suitable for direct imaging, but that’s why simulations give us a rough idea of what the ELTs [Extremely Large Telescopes] would have delivered and the promises they’re meant to hold when they are built,” said Huihao Zhang.

What aspects of an exoplanet should astronomers focus on to find signs of extraterrestrial life? Should they focus on the parent star, the exoplanet’s surface, or something else? This is what a recent study published in The Astronomical Journal hopes to address as a team of researchers from The Ohio State University (OSU) discuss how astronomers could use the next generation of telescopes, specifically the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and other Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs), to conduct more in-depth analyses of an exoplanet’s atmosphere, specifically searching for signs of oxygen and methane, as these are present in the Earth’s atmosphere. This study holds the potential to not only establish criteria for searching for signs of extraterrestrial life, but how astronomers can search for this criterion, as well.

For the study, the researchers used computers models to simulate how an exoplanet’s atmosphere on 10 nearby rocky exoplanets could be analyzed for oxygen, water, methane, and carbon dioxide using what’s known as the direct imaging method with ELTs. The direct imaging method is where astronomers blot out the intense glare from the parent star, making exoplanets orbiting it “appear”, making them easier to identify and study. In the end, the researchers found that GJ 887 b (11 light-years away) was the most promising candidate for detecting biosignatures in its atmosphere while Proxima Centauri b (4.4 light-years away) was found to only be detectable for carbon dioxide.