This essay was also published by the Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies and by Transhumanity under the title “Is Price Performance the Wrong Measure for a Coming Intelligence Explosion?”.

Introduction

Most thinkers speculating on the coming of an intelligence explosion (whether via Artificial-General-Intelligence or Whole-Brain-Emulation/uploading), such as Ray Kurzweil [1] and Hans Moravec [2], typically use computational price performance as the best measure for an impending intelligence explosion (e.g. Kurzweil’s measure is when enough processing power to satisfy his estimates for basic processing power required to simulate the human brain costs $1,000). However, I think a lurking assumption lies here: that it won’t be much of an explosion unless available to the average person. I present a scenario below that may indicate that the imminence of a coming intelligence-explosion is more impacted by basic processing speed – or instructions per second (ISP), regardless of cost or resource requirements per unit of computation, than it is by computational price performance. This scenario also yields some additional, counter-intuitive conclusions, such as that it may be easier (for a given amount of “effort” or funding) to implement WBE+AGI than it would be to implement AGI alone – or rather that using WBE as a mediator of an increase in the rate of progress in AGI may yield an AGI faster or more efficiently per unit of effort or funding than it would be to implement AGI directly.

Loaded Uploads:

Petascale supercomputers in existence today exceed the processing-power requirements estimated by Kurzweil, Moravec, and Storrs-Hall [3]. If a wealthy individual were uploaded onto an petascale supercomputer today, they would have the same computational resources as the average person would eventually have in 2019 according to Kurzweil’s figures, when computational processing power equal to the human brain, which he estimates at 20 quadrillion calculations per second. While we may not yet have the necessary software to emulate a full human nervous system, the bottleneck for being able to do so is progress in the field or neurobiology rather than software performance in general. What is important is that the raw processing power estimated by some has already been surpassed – and the possibility of creating an upload may not have to wait for drastic increases in computational price performance.

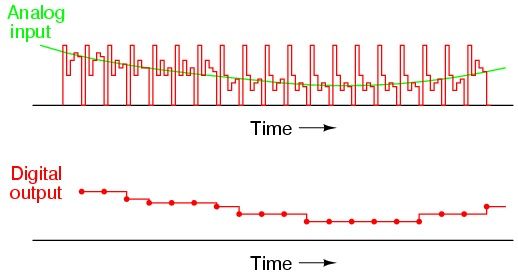

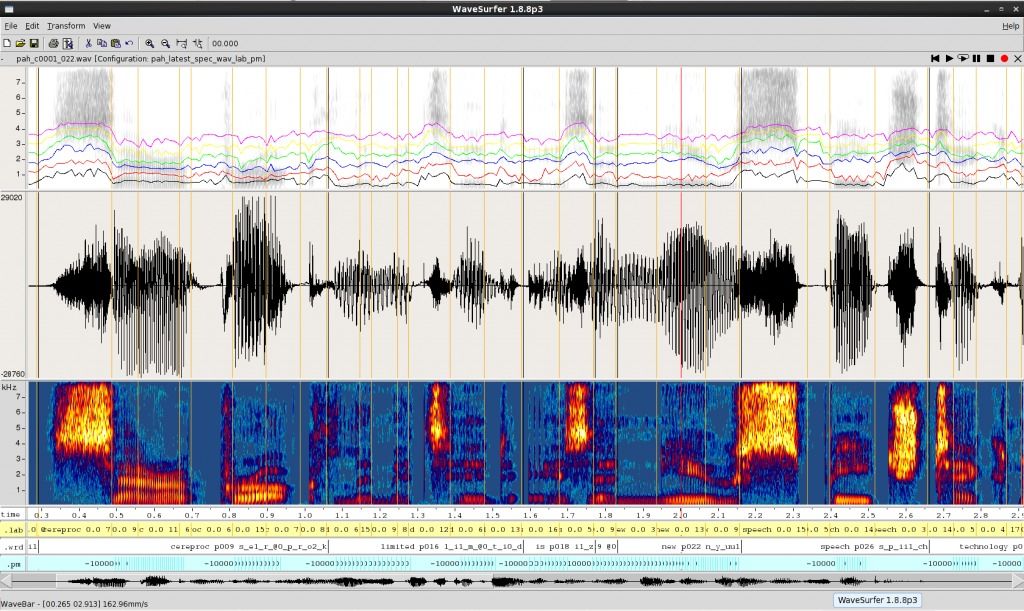

The rate of signal transmission in electronic computers has been estimated to be roughly 1 million times as fast as the signal transmission speed between neurons, which is limited to the rate of passive chemical diffusion. Since the rate of signal transmission equates with subjective perception of time, an upload would presumably experience the passing of time one million times faster than biological humans. If Yudkowsky’s observation [4] that this would be the equivalent to experiencing all of history since Socrates every 18 “real-time” hours is correct then such an emulation would experience 250 subjective years for every hour and 4 years a minute. A day would be equal to 6,000 years, a week would be equal to 1,750 years, and a month would be 75,000 years.

Moreover, these figures use the signal transmission speed of current, electronic paradigms of computation only, and thus the projected increase in signal-transmission speed brought about through the use of alternative computational paradigms, such as 3-dimensional and/or molecular circuitry or Drexler’s nanoscale rod-logic [5], can only be expected to increase such estimates of “subjective speed-up”.

The claim that the subjective perception of time and the “speed of thought” is a function of the signal-transmission speed of the medium or substrate instantiating such thought or facilitating such perception-of-time follows from the scientific-materialist (a.k.a. metaphysical-naturalist) claim that the mind is instantiated by the physical operations of the brain. Thought and perception of time (or the rate at which anything is perceived really) are experiential modalities that constitute a portion of the brain’s cumulative functional modalities. If the functional modalities of the brain are instantiated by the physical operations of the brain, then it follows that increasing the rate at which such physical operations occur would facilitate a corresponding increase in the rate at which such functional modalities would occur, and thus the rate at which the experiential modalities that form a subset of those functional modalities would likewise occur.

Petascale supercomputers have surpassed the rough estimates made by Kurzweil (20 petaflops, or 20 quadrillion calculations per second), Moravec (100,000 MIPS), and others. Most argue that we still need to wait for software improvements to catch up with hardware improvements. Others argue that even if we don’t understand how the operation of the brain’s individual components (e.g. neurons, neural clusters, etc.) converge to create the emergent phenomenon of mind – or even how such components converge so as to create the basic functional modalities of the brain that have nothing to do with subjective experience – we would still be able to create a viable upload. Nick Bostrom & Anders Sandberg, in their 2008 Whole Brain Emulation Roadmap [6] for instance, have argued that if we understand the operational dynamics of the brain’s low-level components, we can then computationally emulate such components and the emergent functional modalities of the brain and the experiential modalities of the mind will emerge therefrom.

Petascale supercomputers have surpassed the rough estimates made by Kurzweil (20 petaflops, or 20 quadrillion calculations per second), Moravec (100,000 MIPS), and others. Most argue that we still need to wait for software improvements to catch up with hardware improvements. Others argue that even if we don’t understand how the operation of the brain’s individual components (e.g. neurons, neural clusters, etc.) converge to create the emergent phenomenon of mind – or even how such components converge so as to create the basic functional modalities of the brain that have nothing to do with subjective experience – we would still be able to create a viable upload. Nick Bostrom & Anders Sandberg, in their 2008 Whole Brain Emulation Roadmap [6] for instance, have argued that if we understand the operational dynamics of the brain’s low-level components, we can then computationally emulate such components and the emergent functional modalities of the brain and the experiential modalities of the mind will emerge therefrom.

Mind Uploading is (Largely) Independent of Software Performance:

Why is this important? Because if we don’t have to understand how the separate functions and operations of the brain’s low-level components converge so as to instantiate the higher-level functions and faculties of brain and mind, then we don’t need to wait for software improvements (or progress in methodological implementation) to catch up with hardware improvements. Note that for the purposes of this essay “software performance” will denote the efficacy of the “methodological implementation” of an AGI or Upload (i.e. designing the mind-in-question, regardless of hardware or “technological implementation” concerns) rather than how optimally software achieves its effect(s) for a given amount of available computational resources.

This means that if the estimates for sufficient processing power to emulate the human brain noted above are correct then a wealthy individual could hypothetically have himself destructively uploaded and run on contemporary petascale computers today, provided that we can simulate the operation of the brain at a small-enough scale (which is easier than simulating components at higher scales; simulating the accurate operation of a single neuron is less complex than simulating the accurate operation of higher-level neural networks or regions). While we may not be able to do so today due to lack of sufficient understanding of the operational dynamics of the brain’s low-level components (and whether the models we currently have are sufficient is an open question), we need wait only for insights from neurobiology, and not for drastic improvements in hardware (if the above estimates for required processing-power are correct), or in software/methodological-implementation.

This means that if the estimates for sufficient processing power to emulate the human brain noted above are correct then a wealthy individual could hypothetically have himself destructively uploaded and run on contemporary petascale computers today, provided that we can simulate the operation of the brain at a small-enough scale (which is easier than simulating components at higher scales; simulating the accurate operation of a single neuron is less complex than simulating the accurate operation of higher-level neural networks or regions). While we may not be able to do so today due to lack of sufficient understanding of the operational dynamics of the brain’s low-level components (and whether the models we currently have are sufficient is an open question), we need wait only for insights from neurobiology, and not for drastic improvements in hardware (if the above estimates for required processing-power are correct), or in software/methodological-implementation.

If emulating the low-level components of the brain (e.g. neurons) will give rise to the emergent mind instantiated thereby, then we don’t actually need to know “how to build a mind” – whereas we do in the case of an AGI (which for the purposes of this essay shall denote AGI not based off of the human or mammalian nervous system, even though an upload might qualify as an AGI according to many people’s definitions). This follows naturally from the conjunction of the premises that 1. the system we wish to emulate already exists and 2. we can create (i.e. computationally emulate) the functional modalities of the whole system by only understanding the operation of the low level-level components’ functional modalities.

Thus, I argue that a wealthy upload who did this could conceivably accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion by such a large degree that it could occur before computational price performance drops to a point where the basic processing power required for such an emulation is available for a widely-affordable price, say for $1,000 as in Kurzweil’s figures.

Such a scenario could make basic processing power, or Instructions-Per-Second, more indicative of an imminent intelligence explosion or hard take-off scenario than computational price performance.

If we can achieve human whole-brain-emulation even one week before we can achieve AGI (the cognitive architecture of which is not based off of the biological human nervous system) and this upload set to work on creating an AGI, then such an upload would have, according to the “subjective-speed-up” factors given above, 1,750 subjective years within which to succeed in designing and implementing an AGI, for every one real-time week normatively-biological AGI workers have to succeed.

The subjective-perception-of-time speed-up alone would be enough to greatly improve his/her ability to accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion. Other features, like increased ease-of-self-modification and the ability to make as many copies of himself as he has processing power to allocate to, only increase his potential to accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion.

This is not to say that we can run an emulation without any software at all. Of course we need software – but we may not need drastic improvements in software, or a reinventing of the wheel in software design

So why should we be able to simulate the human brain without understanding its operational dynamics in exhaustive detail? Are there any other processes or systems amenable to this circumstance, or is the brain unique in this regard?

So why should we be able to simulate the human brain without understanding its operational dynamics in exhaustive detail? Are there any other processes or systems amenable to this circumstance, or is the brain unique in this regard?

There is a simple reason for why this claim seems intuitively doubtful. One would expect that we must understand the underlying principles of a given technology’s operation in in order to implement and maintain it. This is, after all, the case for all other technologies throughout the history of humanity. But the human brain is categorically different in this regard because it already exists.

If, for instance, we found a technology and wished to recreate it, we could do so by copying the arrangement of components. But in order to make any changes to it, or any variations on its basic structure or principals-of-operation, we would need to know how to build it, maintain it, and predictively model it with a fair amount of accuracy. In order to make any new changes, we need to know how such changes will affect the operation of the other components – and this requires being able to predictively model the system. If we don’t understand how changes will impact the rest of the system, then we have no reliable means of implementing any changes.

Thus, if we seek only to copy the brain, and not to modify or augment it in any substantial way, the it is wholly unique in the fact that we don’t need to reverse engineer it’s higher-level operations in order to instantiate it.

This approach should be considered a category separate from reverse-engineering. It would indeed involve a form of reverse-engineering on the scale we seek to simulate (e.g. neurons or neural clusters), but it lacks many features of reverse-engineering by virtue of the fact that we don’t need to understand its operation on all scales. For instance, knowing the operational dynamics of the atoms composing a larger system (e.g. any mechanical system) wouldn’t necessarily translate into knowledge of the operational dynamics of its higher-scale components. The approach mind-uploading falls under, where reverse-engineering at a small enough scale is sufficient to recreate it, provided that we don’t seek to modify its internal operation in any significant way, I will call Blind Replication.

Blind replication disallows any sort of significant modifications, because if one doesn’t understand how processes affect other processes within the system then they have no way of knowing how modifications will change other processes and thus the emergent function(s) of the system. We wouldn’t have a way to translate functional/optimization objectives into changes made to the system that would facilitate them. There are also liability issues, in that one wouldn’t know how the system would work in different circumstances, and would have no guarantee of such systems’ safety or their vicarious consequences. So government couldn’t be sure of the reliability of systems made via Blind Replication, and corporations would have no way of optimizing such systems so as to increase a given performance metric in an effort to increase profits, and indeed would be unable to obtain intellectual property rights over a technology that they cannot describe the inner-workings or “operational dynamics” of.

However, government and private industry wouldn’t be motivated by such factors (that is, ability to optimize certain performance measures, or to ascertain liability) in the first place, if they were to attempt something like this – since they wouldn’t be selling it. The only reason I foresee government or industry being interested in attempting this is if a foreign nation or competitor, respectively, initiated such a project, in which case they might attempt it simply to stay competitive in the case of industry and on equal militaristic defensive/offensive footing in the case of government. But the fact that optimization-of-performance-measures and clear liabilities don’t apply to Blind Replication means that a wealthy individual would be more likely to attempt this, because government and industry have much more to lose in terms of liability, were someone to find out.

However, government and private industry wouldn’t be motivated by such factors (that is, ability to optimize certain performance measures, or to ascertain liability) in the first place, if they were to attempt something like this – since they wouldn’t be selling it. The only reason I foresee government or industry being interested in attempting this is if a foreign nation or competitor, respectively, initiated such a project, in which case they might attempt it simply to stay competitive in the case of industry and on equal militaristic defensive/offensive footing in the case of government. But the fact that optimization-of-performance-measures and clear liabilities don’t apply to Blind Replication means that a wealthy individual would be more likely to attempt this, because government and industry have much more to lose in terms of liability, were someone to find out.

Could Upload+AGI be easier to implement than AGI alone?

This means that the creation of an intelligence with a subjective perception of time significantly greater than unmodified humans (what might be called Ultra-Fast Intelligence) may be more likely to occur via an upload, rather than an AGI, because the creation of an AGI is largely determined by increases in both computational processing and software performance/capability, whereas the creation of an upload may be determined by-and-large by processing-power and thus remain largely independent of the need for significant improvements in software performance or “methodological implementation”

If the premise that such an upload could significantly accelerate a coming intelligence explosion (whether by using his/her comparative advantages to recursively self-modify his/herself, to accelerate innovation and R&D in computational hardware and/or software, or to create a recursively-self-improving AGI) is taken as true, it follows that even the coming of an AGI-mediated intelligence explosion specifically, despite being impacted by software improvements as well as computational processing power, may be more impacted by basic processing power (e.g. IPS) than by computational price performance — and may be more determined by computational processing power than by processing power + software improvements. This is only because uploading is likely to be largely independent of increases in software (i.e. methodological as opposed to technological) performance. Moreover, development in AGI may proceed faster via the vicarious method outlined here – namely having an upload or team of uploads work on the software and/or hardware improvements that AGI relies on – than by directly working on such improvements in “real-time” physicality.

Virtual Advantage:

The increase in subjective perception of time alone (if Yudkowsky’s estimate is correct, a ratio of 250 subjective years for every “real-time” hour) gives him/her a massive advantage. It also would likely allow them to counter-act and negate any attempts made from “real-time” physicality to stop, slow or otherwise deter them.

The increase in subjective perception of time alone (if Yudkowsky’s estimate is correct, a ratio of 250 subjective years for every “real-time” hour) gives him/her a massive advantage. It also would likely allow them to counter-act and negate any attempts made from “real-time” physicality to stop, slow or otherwise deter them.

There is another feature of virtual embodiment that could increase the upload’s ability to accelerate such developments. Neural modification, with which he could optimize his current functional modalities (e.g. what we coarsely call “intelligence”) or increase the metrics underlying them, thus amplifying his existing skills and cognitive faculties (as in Intelligence Amplification or IA), as well as creating categorically new functional modalities, is much easier from within virtual embodiment than it would be in physicality. In virtual embodiment, all such modifications become a methodological, rather than technological, problem. To enact such changes in a physically-embodied nervous system would require designing a system to implement those changes, and actually implementing them according to plan. To enact such changes in a virtually-embodied nervous system requires only a re-organization or re-writing of information. Moreover, in virtual embodiment, any changes could be made, and reversed, whereas in physical embodiment reversing such changes would require, again, designing a method and system of implementing such “reversal-changes” in physicality (thereby necessitating a whole host of other technologies and methodologies) – and if those changes made further unexpected changes, and we can’t easily reverse them, then we may create an infinite regress of changes, wherein changes made to reverse a given modification in turn creates more changes, that in turn need to be reversed, ad infinitum.

Thus self-modification (and especially recursive self-modification), towards the purpose of intelligence amplification into Ultraintelligence [7] in easier (i.e. necessitating a smaller technological and methodological infrastructure – that is, the required host of methods and technologies needed by something – and thus less cost as well) in virtual embodiment than in physical embodiment.

These recursive modifications not only further maximize the upload’s ability to think of ways to accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion, but also maximize his ability to further self-modify towards that very objective (thus creating the positive feedback loop critical for I.J Good’s intelligence explosion hypothesis) – or in other words maximize his ability to maximize his general ability in anything.

But to what extent is the ability to self-modify hampered by the critical feature of Blind Replication mentioned above – namely, the inability to modify and optimize various performance measures by virtue of the fact that we can’t predictively model the operational dynamics of the system-in-question? Well, an upload could copy himself, enact any modifications, and see the results – or indeed, make a copy to perform this change-and-check procedure. If the inability to predictively model a system made through the “Blind Replication” method does indeed problematize the upload’s ability to self-modify, it would still be much easier to work towards being able to predictively model it, via this iterative change-and-check method, due to both the subjective-perception-of-time speedup and the ability to make copies of himself.

It is worth noting that it might be possible to predictively model (and thus make reliable or stable changes to) the operation of neurons, without being able to model how this scales up to the operational dynamics of the higher-level neural regions. Thus modifying, increasing or optimizing existing functional modalities (i.e. increasing synaptic density in neurons, or increasing the range of usable neurotransmitters — thus increasing the potential information density in a given signal or synaptic-transmission) may be significantly easier than creating categorically new functional modalities.

Increasing the Imminence of an Intelligent Explosion:

So what ways could the upload use his/her new advantages and abilities to actually accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion? He could apply his abilities to self-modification, or to the creation of a Seed-AI (or more technically a recursively self-modifying AI).

So what ways could the upload use his/her new advantages and abilities to actually accelerate the coming of an intelligence explosion? He could apply his abilities to self-modification, or to the creation of a Seed-AI (or more technically a recursively self-modifying AI).

He could also accelerate its imminence vicariously by working on accelerating the foundational technologies and methodologies (or in other words the technological and methodological infrastructure of an intelligence explosion) that largely determine its imminence. He could apply his new abilities and advantages to designing better computational paradigms, new methodologies within existing paradigms (e.g. non-Von-Neumann architectures still within the paradigm of electrical computation), or to differential technological development in “real-time” physicality towards such aims – e.g. finding an innovative means of allocating assets and resources (i.e. capital) to R&D for new computational paradigms, or optimizing current computational paradigms.

Thus there are numerous methods of indirectly increasing the imminence (or the likelihood of imminence within a certain time-range, which is a measure with less ambiguity) of a coming intelligence explosion – and many new ones no doubt that will be realized only once such an upload acquires such advantages and abilities.

Intimations of Implications:

So… Is this good news or bad news? Like much else in this increasingly future-dominated age, the consequences of this scenario remain morally ambiguous. It could be both bad and good news. But the answer to this question is independent of the premises – that is, two can agree on the viability of the premises and reasoning of the scenario, while drawing opposite conclusions in terms of whether it is good or bad news.

People who subscribe to the “Friendly AI” camp of AI-related existential risk will be at once hopeful and dismayed. While it might increase their ability to create their AGI (or more technically their Coherent-Extrapolated-Volition Engine [8]), thus decreasing the chances of an “unfriendly” AI being created in the interim, they will also be dismayed by the fact that it may include (but not necessitate) a recursively-modifying intelligence, in this case an upload, to be created prior to the creation of their own AGI – which is the very problem they are trying to mitigate in the first place.

People who subscribe to the “Friendly AI” camp of AI-related existential risk will be at once hopeful and dismayed. While it might increase their ability to create their AGI (or more technically their Coherent-Extrapolated-Volition Engine [8]), thus decreasing the chances of an “unfriendly” AI being created in the interim, they will also be dismayed by the fact that it may include (but not necessitate) a recursively-modifying intelligence, in this case an upload, to be created prior to the creation of their own AGI – which is the very problem they are trying to mitigate in the first place.

Those who, like me, see a distributed intelligence explosion (in which all intelligences are allowed to recursively self-modify at the same rate – thus preserving “power” equality, or at least mitigating “power” disparity [where power is defined as the capacity to affect change in the world or society] – and in which any intelligence increasing their capably at a faster rate than all others is disallowed) as a better method of mitigating the existential risk entailed by an intelligence explosion will also be dismayed. This scenario would allow one single person to essentially have the power to determine the fate of humanity – due to his massively increased “capability” or “power” – which is the very feature (capability disparity/inequality) that the “distributed intelligence explosion” camp of AI-related existential risk seeks to minimize.

On the other hand, those who see great potential in an intelligence explosion to help mitigate existing problems afflicting humanity – e.g. death, disease, societal instability, etc. – will be hopeful because the scenario could decrease the time it takes to implement an intelligence explosion.

I for one think that it is highly likely that the advantages proffered by accelerating the coming of an intelligence explosion fail to supersede the disadvantages incurred by the increase existential risk it would entail. That is, I think that the increase in existential risk brought about by putting so much “power” or “capability-to-affect-change” in the (hands?) one intelligence outweighs the decrease in existential risk brought about by the accelerated creation of an Existential-Risk-Mitigating A(G)I.

Conclusion:

Thus, the scenario presented above yields some interesting and counter-intuitive conclusions:

How imminent an intelligence explosion is, or how likely it is to occur within a given time-frame, may be more determined by basic processing power than by computational price performance, which is a measure of basic processing power per unit of cost. This is because as soon as we have enough processing power to emulate a human nervous system, provided we have sufficient software to emulate the lower level neural components giving rise to the higher-level human mind, then the increase in the rate of thought and subjective perception of time made available to that emulation could very well allow it to design and implement an AGI before computational price performance increases by a large enough factor to make the processing power necessary for that AGI’s implementation available for a widely-affordable cost. This conclusion is independent of any specific estimates of how long the successful computational emulation of a human nervous system will take to achieve. It relies solely on the premise that the successful computational emulation of the human mind can be achieved faster than the successful implementation of an AGI whose design is not based upon the cognitive architecture of the human nervous system. I have outlined various reasons why we might expect this to be the case. This would be true even if uploading could only be achieved faster than AGI (given an equal amount of funding or “effort”) by a seemingly-negligible amount of time, like one week, due to the massive increase in speed of thought and the rate of subjective perception of time that would then be available to such an upload.

How imminent an intelligence explosion is, or how likely it is to occur within a given time-frame, may be more determined by basic processing power than by computational price performance, which is a measure of basic processing power per unit of cost. This is because as soon as we have enough processing power to emulate a human nervous system, provided we have sufficient software to emulate the lower level neural components giving rise to the higher-level human mind, then the increase in the rate of thought and subjective perception of time made available to that emulation could very well allow it to design and implement an AGI before computational price performance increases by a large enough factor to make the processing power necessary for that AGI’s implementation available for a widely-affordable cost. This conclusion is independent of any specific estimates of how long the successful computational emulation of a human nervous system will take to achieve. It relies solely on the premise that the successful computational emulation of the human mind can be achieved faster than the successful implementation of an AGI whose design is not based upon the cognitive architecture of the human nervous system. I have outlined various reasons why we might expect this to be the case. This would be true even if uploading could only be achieved faster than AGI (given an equal amount of funding or “effort”) by a seemingly-negligible amount of time, like one week, due to the massive increase in speed of thought and the rate of subjective perception of time that would then be available to such an upload.- The creation of an upload may be relatively independent of software performance/capability (which is not to say that we don’t need any software, because we do, but rather that we don’t need significant increases in software performance or improvements in methodological implementation – i.e. how we actually design a mind, rather than the substrate it is instantiated by – which we do need in order to implement an AGI and which we would need for WBE, were the system we seek to emulate not already in existence) and may in fact be largely determined by processing power or computational performance/capability alone, whereas AGI is dependent on increases in both computational performance and software performance or fundamental progress in methodological implementation.

- If this second conclusion is true, it means that an upload may be possible quite soon considering the fact that we’ve passed the basic estimates for processing requirements given by Kurzweil, Moravec and Storrs-Hall, provided we can emulate the low-level neural regions of the brain with high predictive accuracy (and provided the claim that instantiating such low-level components will vicariously instantiate the emergent human mind, without out needing to really understand how such components functionally-converge to do so, proves true), whereas AGI may still have to wait for fundamental improvements to methodological implementation or “software performance”

- Thus it may be easier to create an AGI by first creating an upload to accelerate the development of that AGI’s creation, than it would be to work on the development of an AGI directly. Upload+AGI may actually be easier to implement than AGI alone is!

References:

[1] Kurzweil, R, 2005. The Singularity is Near. Penguin Books.

[2] Moravec, H, 1997. When will computer hardware match the human brain?. Journal of Evolution and Technology, [Online]. 1(1). Available at: http://www.jetpress.org/volume1/moravec.htm [Accessed 01 March 2013].

[3] Hall, J (2006) “Runaway Artificial Intelligence?” Available at: http://www.kurzweilai.net/runaway-artificial-intelligence [Accessed: 01 March 2013]

[4] Adam Ford. (2011). Yudkowsky vs Hanson on the Intelligence Explosion — Jane Street Debate 2011 . [Online Video]. August 10, 2011. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m_R5Z4_khNw [Accessed: 01 March 2013].

[5] Drexler, K.E, (1989). MOLECULAR MANIPULATION and MOLECULAR COMPUTATION. In NanoCon Northwest regional nanotechnology conference. Seattle, Washington, February 14–17. NANOCON. 2. http://www.halcyon.com/nanojbl/NanoConProc/nanocon2.html [Accessed 01 March 2013]

[6] Sandberg, A. & Bostrom, N. (2008). Whole Brain Emulation: A Roadmap, Technical Report #2008–3. http://www.philosophy.ox.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/3…report.pdf [Accessed 01 March 2013]

[7] Good, I.J. (1965). Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine. Advances in Computers.

[8] Yudkowsky, E. (2004). Coherent Extrapolated Volition. The Singularity Institute.