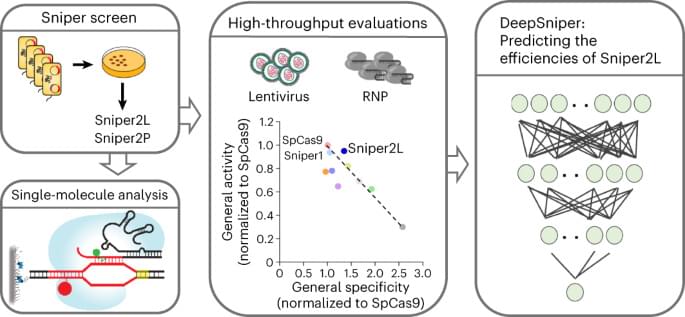

Kim et al. used directed evolution methods to identify a high-fidelity SpCas9 variant, Sniper2L, which exhibits high general activity but maintains high specificity at a large number of target sites.

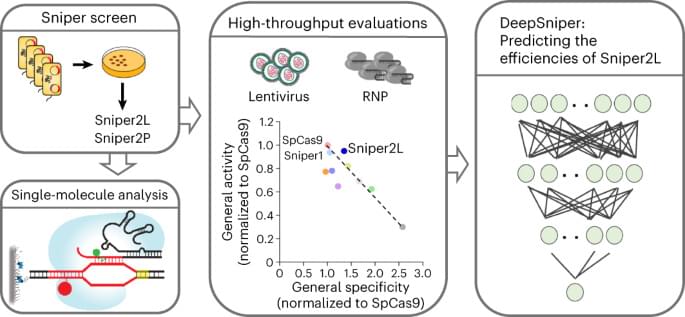

The inner workings of our planet are getting weirder.

For generations, scientists have probed the structure and composition of the planet using seismic wave studies. This consists of measuring shock waves caused by earthquakes as they penetrate and pass through the Earth’s core region. By noting differences in speed (a process known as anisotropy), scientists can determine which regions are denser than others. These studies have led to the predominant geological model that incorporates four distinct layers: a crust and a mantle (composed largely of silicate minerals) and an outer core and inner core composed of nickel-iron.

According to seismologists from The Australian National University (ANU), data obtained in a recent study has shed new light on the deepest parts of Earth’s inner core. In a paper that appeared in Nature Communications, the team reports finding evidence for another distinct layer (a solid metal ball) in the center of Earth’s inner core — an “innermost inner core.” These findings could shed new light on the evolution of our planet and lead to revised geological models of Earth that include five distinct layers instead of the traditional four.

The research was led by Dr. Thanh-Son Pham and Dr. Hrvoje Tkalcic, a postdoctoral fellow and professor with ANU’s Research School of Earth Sciences (RSES), respectively. As they indicate, the team stacked seismic wave data from about 200 earthquakes in the past decade that were magnitude-6 or more. The triggered waveforms were recorded by seismic stations worldwide, which traveled directly through the Earth’s center to the opposite side of the globe (the antipode) before traveling back to the source of the earthquake.

The cosmos is full of mysteries, one of which is the existence of supermassive black holes. Though much effort has been granted to these celestial mysteries, the evolution and formation of such supermassive black holes are quite hard to explain.

Supermassive Black Holes

According to Science Alert, these celestial objects are among the heaviest in the entire universe. In fact, their mass can be up to millions or billions of times that of the sun. They can have the mass of more than 10 billion suns, and this is not just in theory.

The concept of Boltzmann Brain — a self-aware entity that emerges from random fluctuations in the fabric of reality— is intriguing. Perhaps God emerges from the evolution of a cosmic society of Boltzmann Brains?

I am referring to a generic “fabric of reality” but the concept can be formulated more precisely. For example, imagine a conscious, thinking being arising from random quantum fluctuations in the vacuum.

In the delightful “The Gravity Mine” short story, Stephen Baxter imagines the birth of a Boltzmann Brain:

However, this picture, which depicts the evolution of man, may actually pose a danger to our general understanding of how evolution plays out on the planet. One might interpret the picture as: Evolution is a unidirectional, progressive process for the betterment of species. This, in fact could not be farther from the truth.

So, what is evolution exactly?

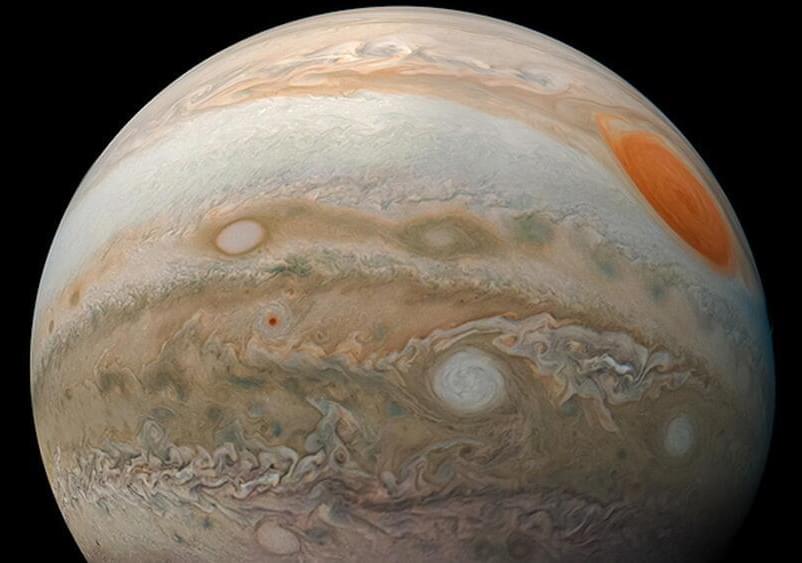

New simulations paint a picture of our solar system resembling an ornate clock. “Throw more gears into the mix and it all breaks.”

A new experiment shed new light on the role Jupiter has played in the evolution of life on Earth. In a series of simulations, scientists showed that an Earth-like planet orbiting between Mars and Jupiter would be able to alter Earth’s orbit and push it out of the solar system.

Such an event would extricate Earth from its life support system, the Sun, and would therefore wipe out all life on our planet.

Ultimately, the experiment highlighted how the solar system’s largest gas giant, Jupiter, plays a crucial role in stabilizing the orbits of its surrounding planets. The hypothetical scenario was considered as part of a UC Riverside experiment.

Brave new world let’s create happiness for everyone by putting microelectrode arrays in our brains but be careful not to create a situation like death by ecstacy by Larry Niven.

In the brain, pleasure is generated by a handful of brain regions called, “hedonic hotspots.” If you were to stimulate these regions directly, you would likely feel pleasurable sensations. However, not all of the hedonic hotspots are the same–some generate the raw sensations of pleasure whereas others are responsible for consciously interpreting and elaborating on the raw pleasure produced by the other hotspots. In this video, in addition to exploring the neuroscience of pleasure, we’ll see how understanding pleasure, happiness, meaning, and purpose can help us live better lives.

Follow @senseofmindshow for more neuroscience explainers.

Follow on Social Media: https://linktr.ee/senseofmind.

-

Chapters.

00:00 Hedonic hotspots: the brain’s pleasure generators.

00:56 The evolution of pleasure.

01:46 How the brain generates pleasure.

03:07 The subcortical (‘core’) pleasure network.

04:08 The cortical (‘higher’) pleasure network.

05:09 The orbitofrontal cortex’ role and the abstract to concrete pleasure gradient.

08:13 How to be happier by understanding the neuroscience of pleasure.

11:40 Summary.

-

This story comes from our special January 2021 issue, “The Beginning and the End of the Universe.” Click here to purchase the full issue.

By studying this cosmic dawn, Mobasher hopes to answer fundamental questions about our universe today. Understanding the dark ages “would help us understand how galaxies are formed, how stars are formed, the evolution of galaxies through the universe,” he says. “How our own galaxy started, how it was formed, how fast it built up stars … all those questions are important questions we need to answer.”

At least, that was the assumption in the second half of the 19th century. This scenario became known as the “heat death” of the universe, and it seemed to be the nail in the coffin for any optimistic cosmology that promised, or even allowed, eternal life and consciousness. For example, one of the most popular cosmological models of the time was put forth by the evolutionary theorist Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Charles Darwin who was actually more famous than him during their time. Spencer believed that the flow of energy through the universe was organizing it. He argued that biological evolution was just part of a larger process of cosmic evolution, and that life and human civilization were the current products of a process of continual cosmic complexification, which would ultimately lead to a state of maximal complexity, integration and balance among all things.

When the prominent Irish physicist John Tyndall told Spencer about the heat death hypothesis in a letter in 1858,” Spencer wrote him back to say it left him “staggered”: “Indeed, not seeing my way out of the conclusion, I remember being out of spirits for some days afterwards. I still feel unsettled about the matter.”

Things got even gloomier when the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann put forward a new statistical interpretation of the second law in the latter half of the 19th century. That was when the idea that the universe is growing more disordered came into the picture. Boltzmann took the classical version of the second law — that useful energy inevitably dissipates — and tried to give it a statistical explanation on the level of molecules colliding and spreading out. He used one of the simplest models possible: a gas confined to a box.