A new study reveals that close friendships can synchronize brain activity and influence decision-making, particularly in consumer behavior.

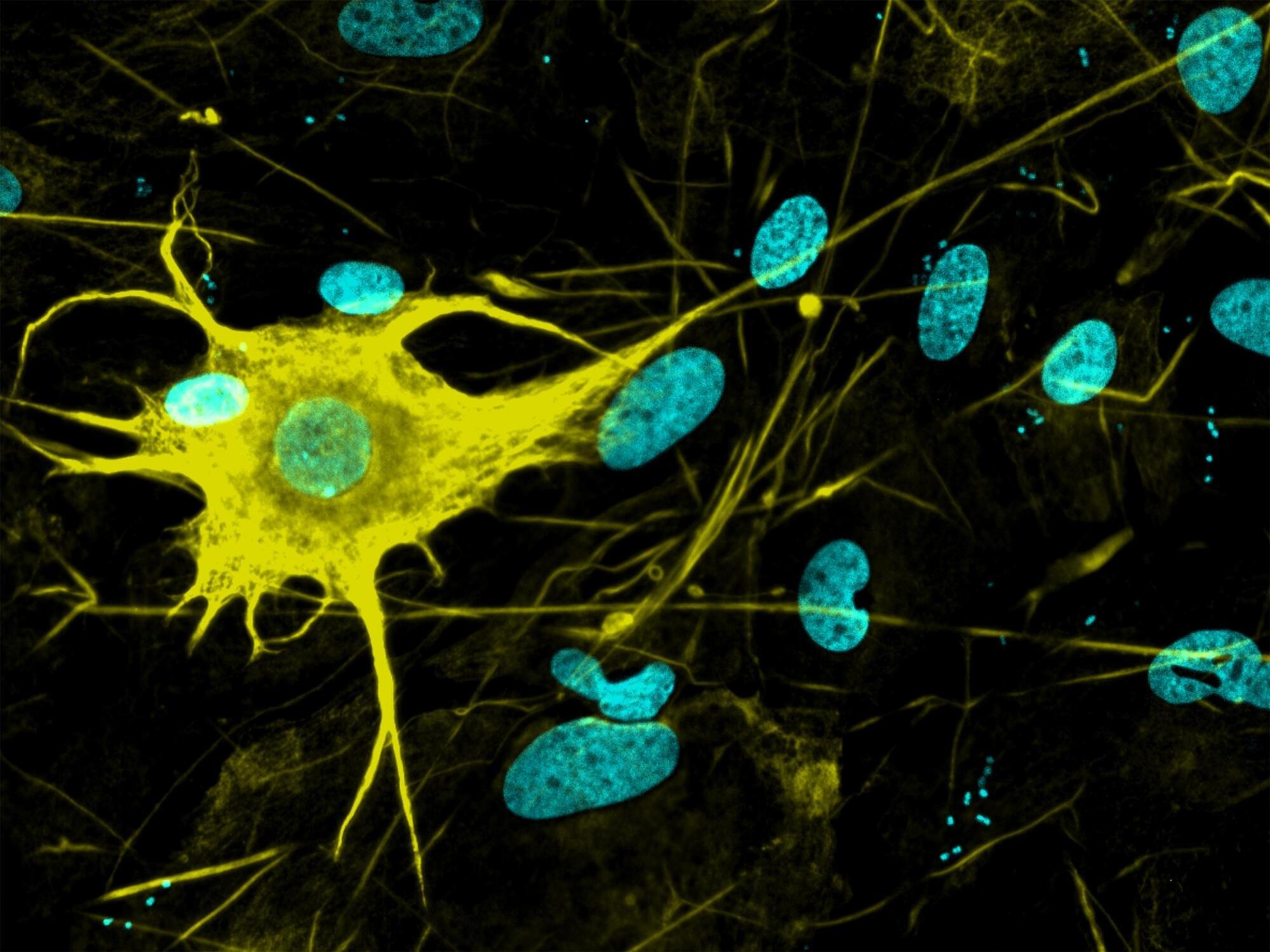

Michael Graziano is a scientist and novelist who is currently a Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Princeton University. He’s a best-selling author and has written several books including “Consciousness and the Social Brain”, “Re-thinking Consciousness”, “The Spaces Between Us”, and much more. His scientific research at Graziano Lab focuses on the brain basis of awareness. He has proposed the “attention schema theory” (AST), an explanation of how, and for what adaptive advantage, brains attribute the property of awareness to themselves.

TIMESTAMPS:

0:00 — Introduction.

2:12 — Meet Dr Michael Graziano: The Consciousness Theorist.

6:44 — What Is Consciousness? A Deep Dive.

11:35 — The Illusion of Consciousness.

15:20 — Attention Schema Theory.

20:05 — Mystery of Self-Awareness and the ‘I’

25:10 — The Hard Problem vs. the Meta Problem of Consciousness.

30:55 — Social Awareness & Dehumanization.

34:20 — Effect of Social Media on Human Interaction.

38:05 — Role of Attention in Machine Consciousness.

41:55 — Creating an AI Mind: Step by Step Guide.

47:30 — Exploring the Building Blocks of Artificial Consciousness.

51:15 — AI Self-Perception: Can Machines Be Conscious?

56:10 — Challenging the Magical vs. Scientific View of Consciousness.

1:00:40 — Consciousness: A Choice Between Magic and Science?

1:05:12 — Attention in Machine Learning: A Closer Look.

1:10:55 — The Psychology of Human Perception.

1:14:20 — Social Awareness and the Digital Revolution.

1:18:35 — Conclusion.

EPISODE LINKS:

Michael’s Website: https://grazianolab.princeton.edu/

Michael’s Books: https://tinyurl.com/2eufd62r.

TED-ed \

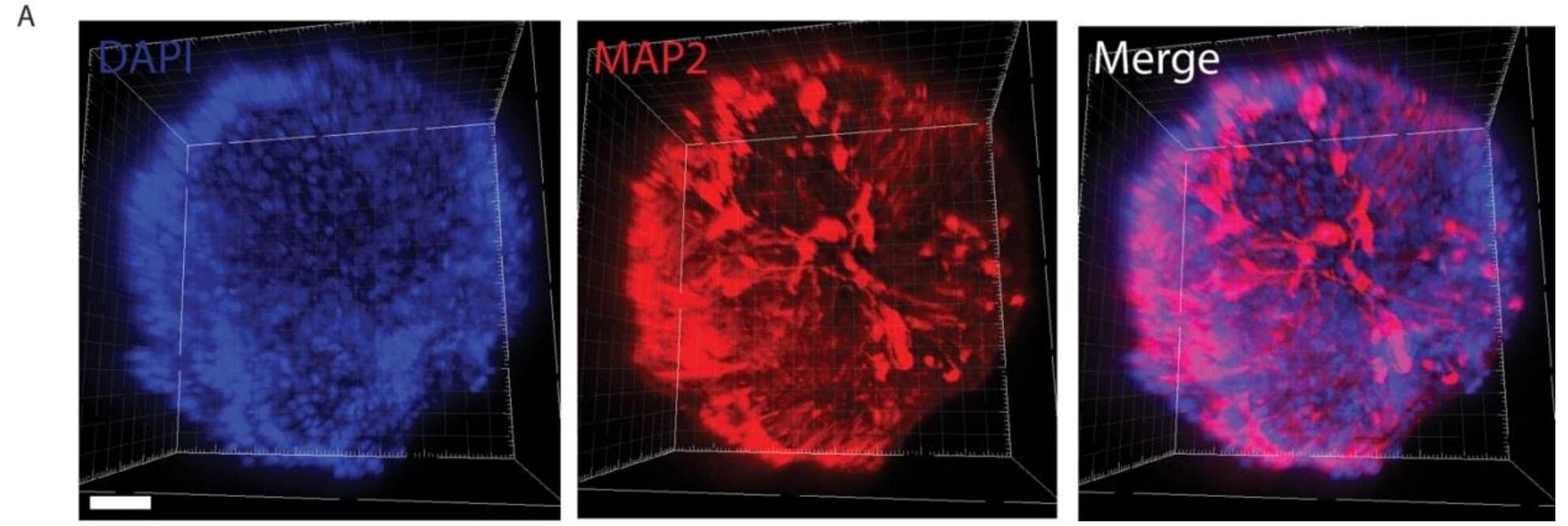

A new Yale study has found a promising target for treating the brain fog that can follow COVID-19 and offers new insight into a hypothesis about the origin of Alzheimer’s disease.

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease is the presence of plaque formed by the buildup of amyloid beta peptides (short chains of amino acids) in and around brain cells. Some researchers suspect that amyloid beta, which is structurally similar to antimicrobial peptides, protects the brain against bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungal infections. Because the blood-brain barrier tends to lose its integrity in Alzheimer’s disease patients, the accumulation of amyloid beta might be a signal that pathogens are infiltrating the brain.

In a new study published in Science Advances, Yale researchers investigated whether infection by SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—can trigger Alzheimer’s disease-like amyloid beta buildup, leading to neurological impairments like brain fog.