Perovskite solar cells are among the most promising candidates for the next generation of photovoltaics: lightweight, flexible, and potentially very low-cost. However, their tendency to degrade under sunlight and heat has so far limited widespread adoption. Now, a new study published in Joule presents an innovative and scalable strategy to overcome this key limitation.

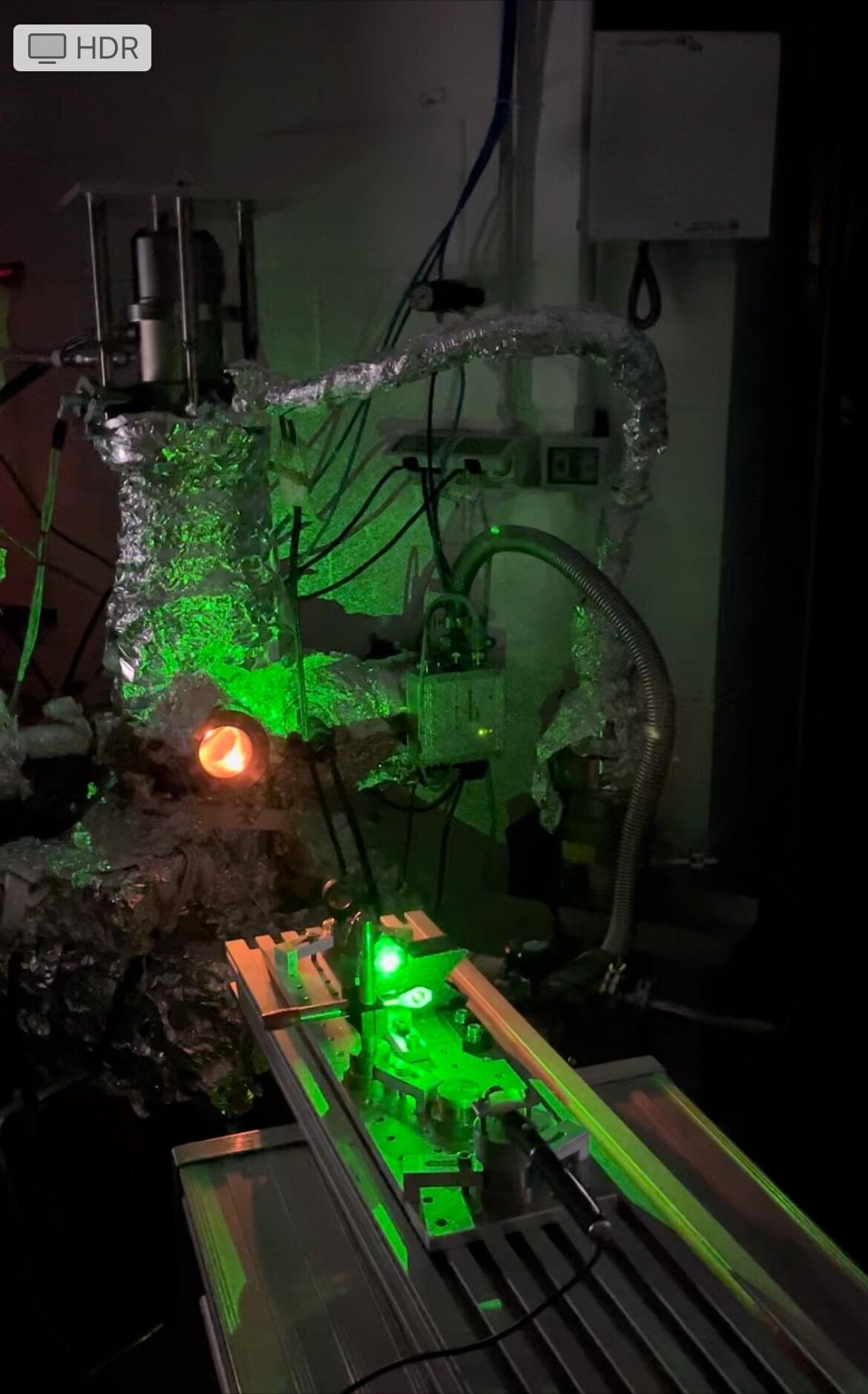

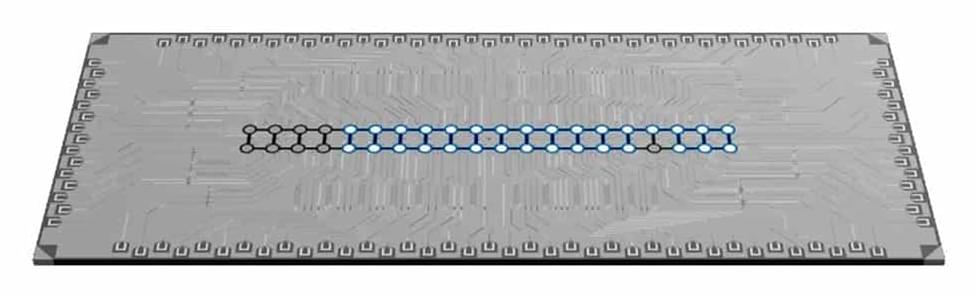

A research team led by the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), in collaboration with the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland (HES-SO) and the Politecnico di Milano, has developed a bulk passivation technique that involves adding the molecule TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) to the perovskite film and applying a brief infrared heating pulse lasting just half a second.

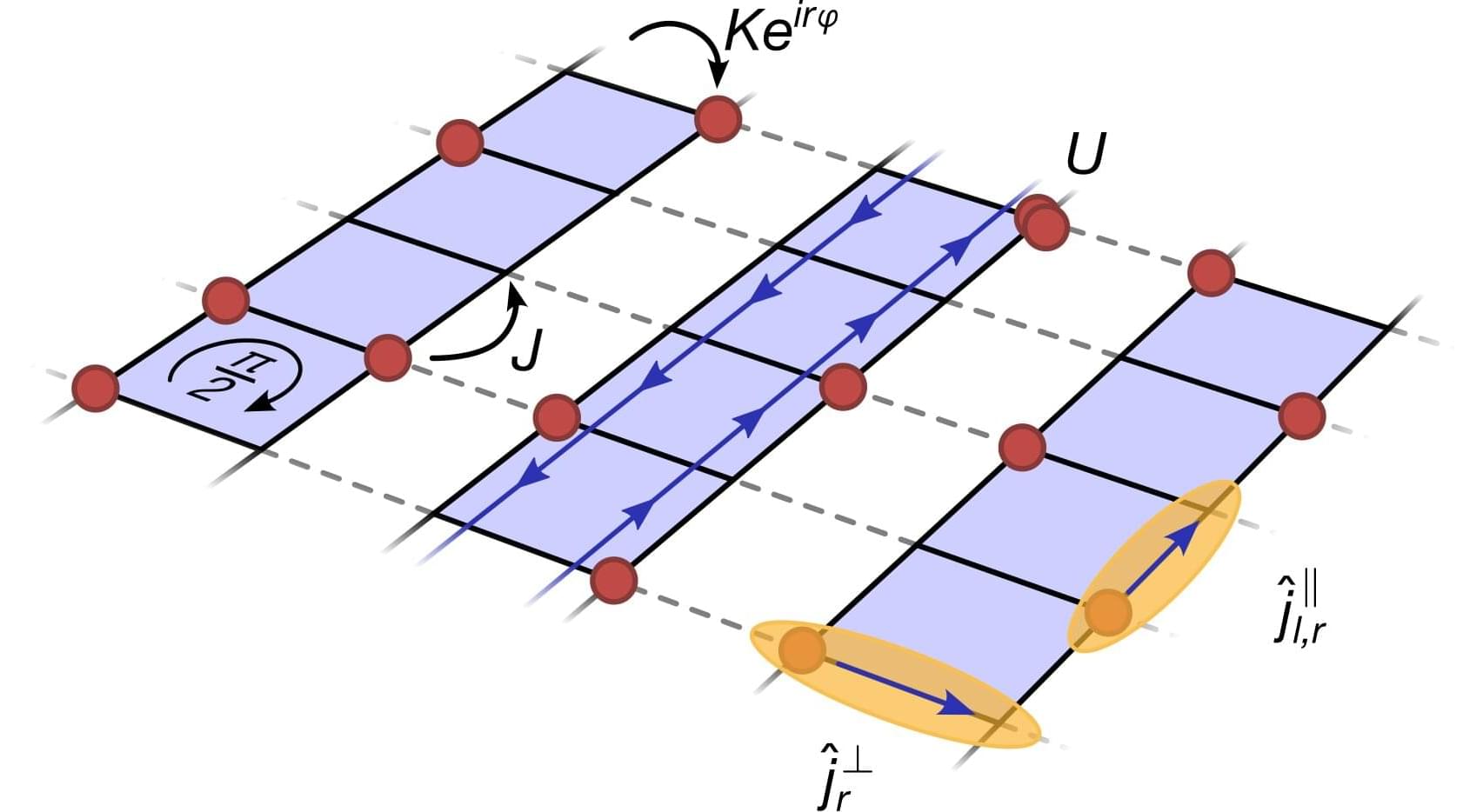

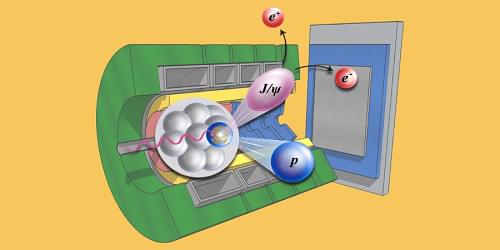

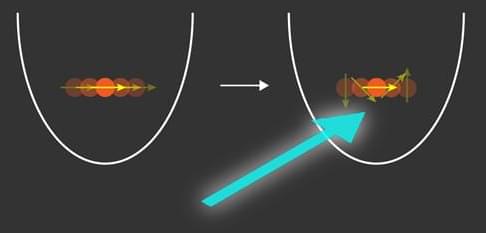

This approach enables the repair of near-invisible crystalline defects inside the material, boosting solar cell efficiency beyond 20% and maintaining that performance for several months under operating conditions. Using positron annihilation spectroscopy—a method involving antimatter particles that probe atomic-scale defects—the researchers confirmed a significant reduction in vacancy-type defects.