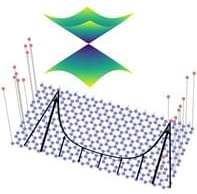

A quantum Monte Carlo calculation shows that the hydrodynamic behavior of the charge current at graphene’s charge neutrality point can emerge despite the absence of momentum flow.

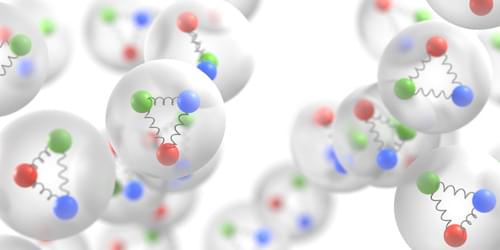

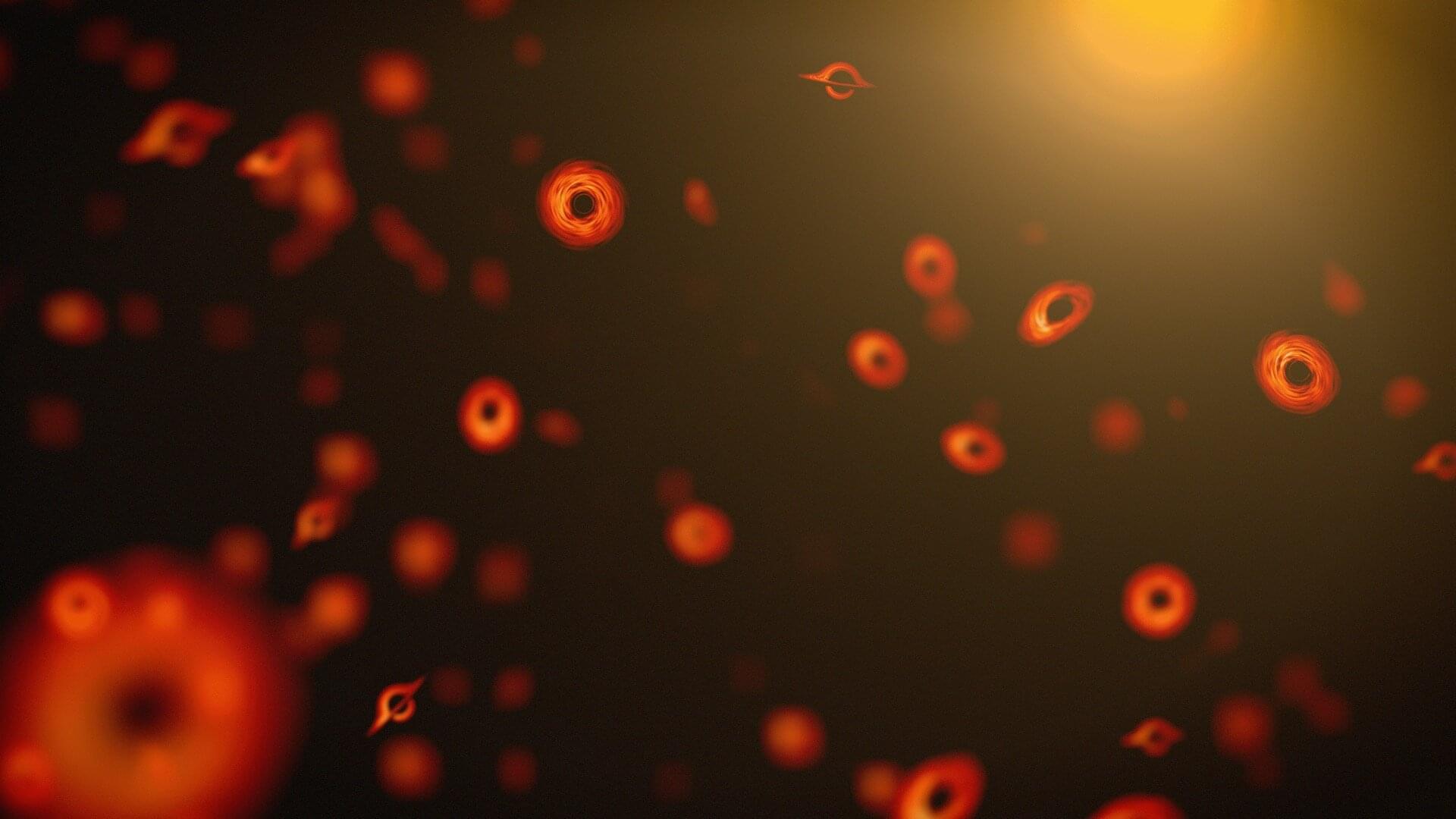

Besides particles like sterile neutrinos, axions and weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), a leading candidate for the cold dark matter of the universe are primordial black holes—black holes created from extremely dense conglomerations of subatomic particles in the first seconds after the Big Bang.

Primordial black holes (PBHs) are classically stable, but as shown by Stephen Hawking in 1975, they can evaporate via quantum effects, radiating nearly like a blackbody. Thus, they have a lifetime; it’s proportional to the cube of their initial mass. As it’s been 13.8 billion years since the Big Bang, only PBHs with an initial mass of a trillion kilograms or more should have survived to today.

However, it has been suggested that the lifetime of a black hole might be considerably longer than Hawking’s prediction due to the memory burden effect, where the load of information carried by a black hole stabilizes it against evaporation.

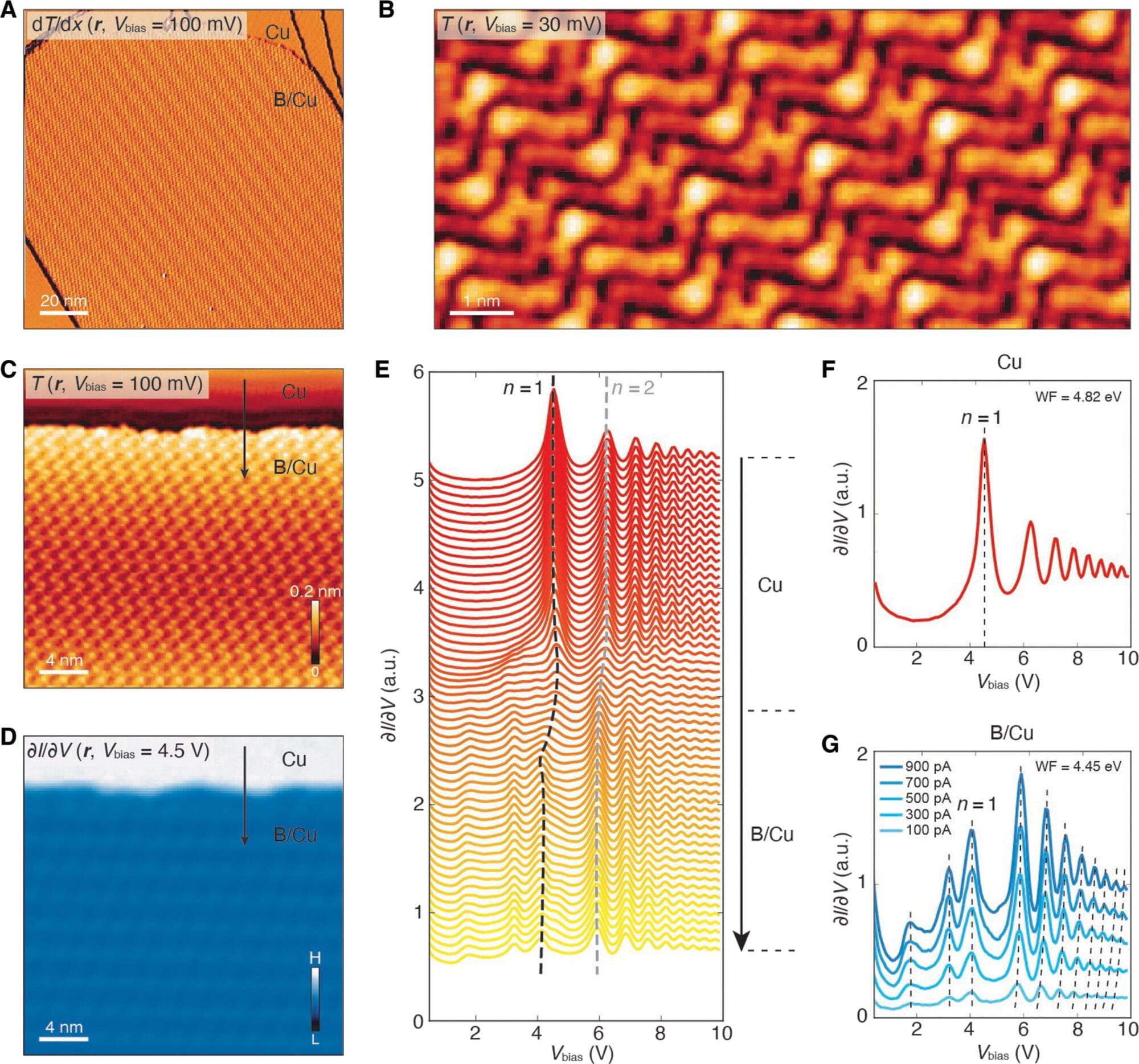

More than ten years ago, researchers at Rice University led by materials scientist Boris Yakobson predicted that boron atoms would cling too tightly to copper to form borophene, a flexible, metallic two-dimensional material with potential across electronics, energy and catalysis. Now, new research shows that prediction holds up, but not in the way anyone expected.

Unlike systems such as graphene on copper, where atoms may diffuse into the substrate without forming a distinct alloy, the boron atoms in this case formed a defined 2D copper boride ⎯ a new compound with a distinct atomic structure. The finding, published in Science Advances by researchers from Rice and Northwestern University, sets the stage for further exploration of a relatively untapped class of 2D materials.

“Borophene is still a material at the brink of existence, and that makes any new fact about it important by pushing the envelope of our knowledge in materials, physics and electronics,” said Yakobson, Rice’s Karl F. Hasselmann Professor of Engineering and professor of materials science and nanoengineering and chemistry. “Our very first theoretical analysis warned that on copper, boron would bond too strongly. Now, more than a decade later, it turns out we were right ⎯ and the result is not borophene, but something else entirely.”

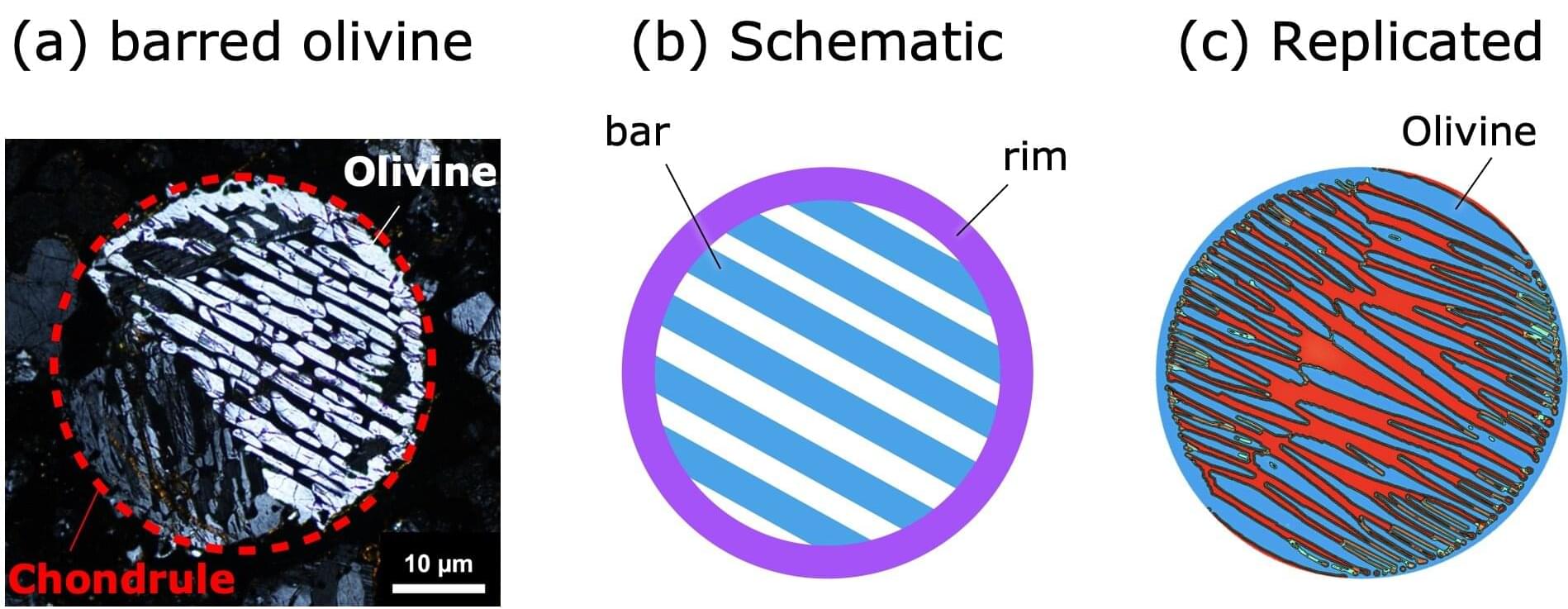

Researchers from Nagoya City University, Tohoku University, and other institutions have used numerical simulations to replicate how a peculiar mineral texture called barred olivine forms inside chondrules—millimeter-sized spherical particles found in meteorites. These chondrules are considered time capsules from the early solar system, and barred olivine is a rare mineral texture not seen in Earth rocks.

The study is published in Science Advances.

Associate Professor Hitoshi Miura of Nagoya City University and the team were the first to reproduce this texture using numerical simulations and theoretically elucidate its formation process.

Perovskite solar cells are among the most promising candidates for the next generation of photovoltaics: lightweight, flexible, and potentially very low-cost. However, their tendency to degrade under sunlight and heat has so far limited widespread adoption. Now, a new study published in Joule presents an innovative and scalable strategy to overcome this key limitation.

A research team led by the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), in collaboration with the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland (HES-SO) and the Politecnico di Milano, has developed a bulk passivation technique that involves adding the molecule TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) to the perovskite film and applying a brief infrared heating pulse lasting just half a second.

This approach enables the repair of near-invisible crystalline defects inside the material, boosting solar cell efficiency beyond 20% and maintaining that performance for several months under operating conditions. Using positron annihilation spectroscopy—a method involving antimatter particles that probe atomic-scale defects—the researchers confirmed a significant reduction in vacancy-type defects.

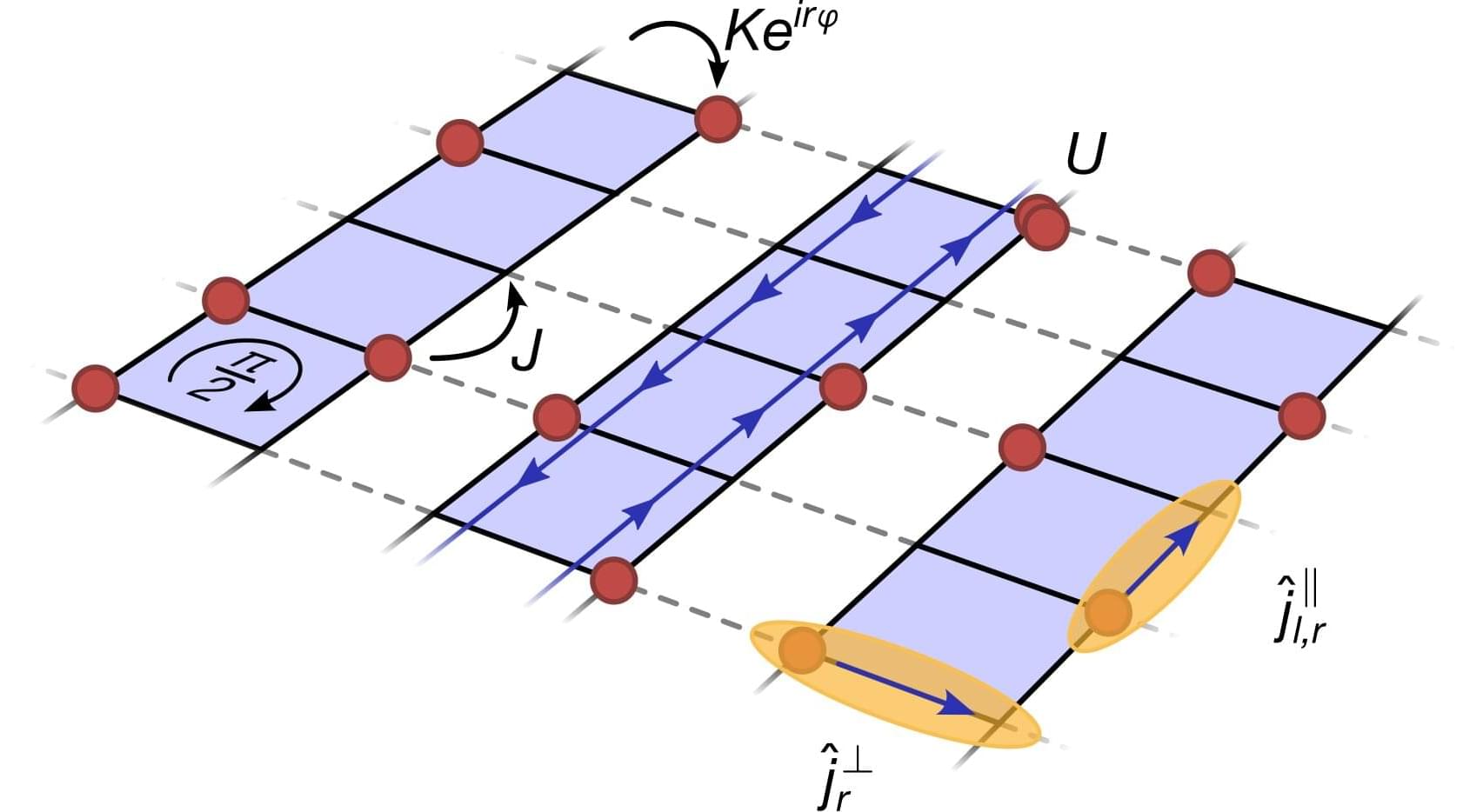

Thus, a complete understanding of quantum transport requires the ability to simulate and probe macroscopic and microscopic physics on equal footing.

Researchers from Singapore and China have utilized a superconducting quantum processor to examine the phenomenon of quantum transport in unprecedented detail.

Gaining deeper insights into quantum transport—encompassing the flow of particles, magnetization, energy, and information through quantum channels—has the potential to drive significant innovations in next-generation technologies such as nanoelectronics and thermal management.

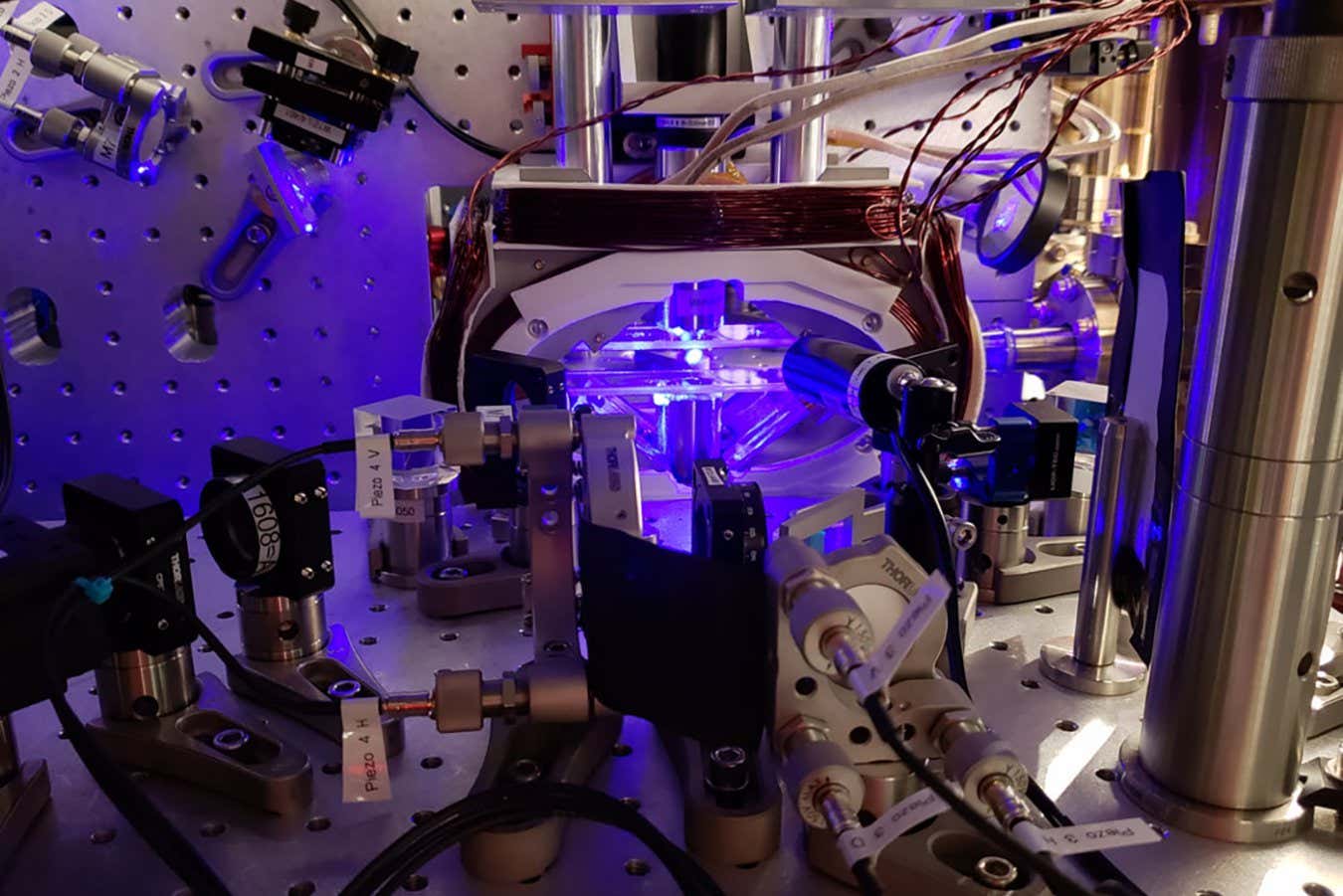

When exposed to periodic driving, which is the time-dependent manipulation of a system’s parameters, quantum systems can exhibit interesting new phases of matter that are not present in time-independent (i.e., static) conditions. Among other things, periodic driving can be useful for the engineering of synthetic gauge fields, artificial constructs that mimic the behavior of electromagnetic fields and can be leveraged to study topological many-body physics using neutral atom quantum simulators.

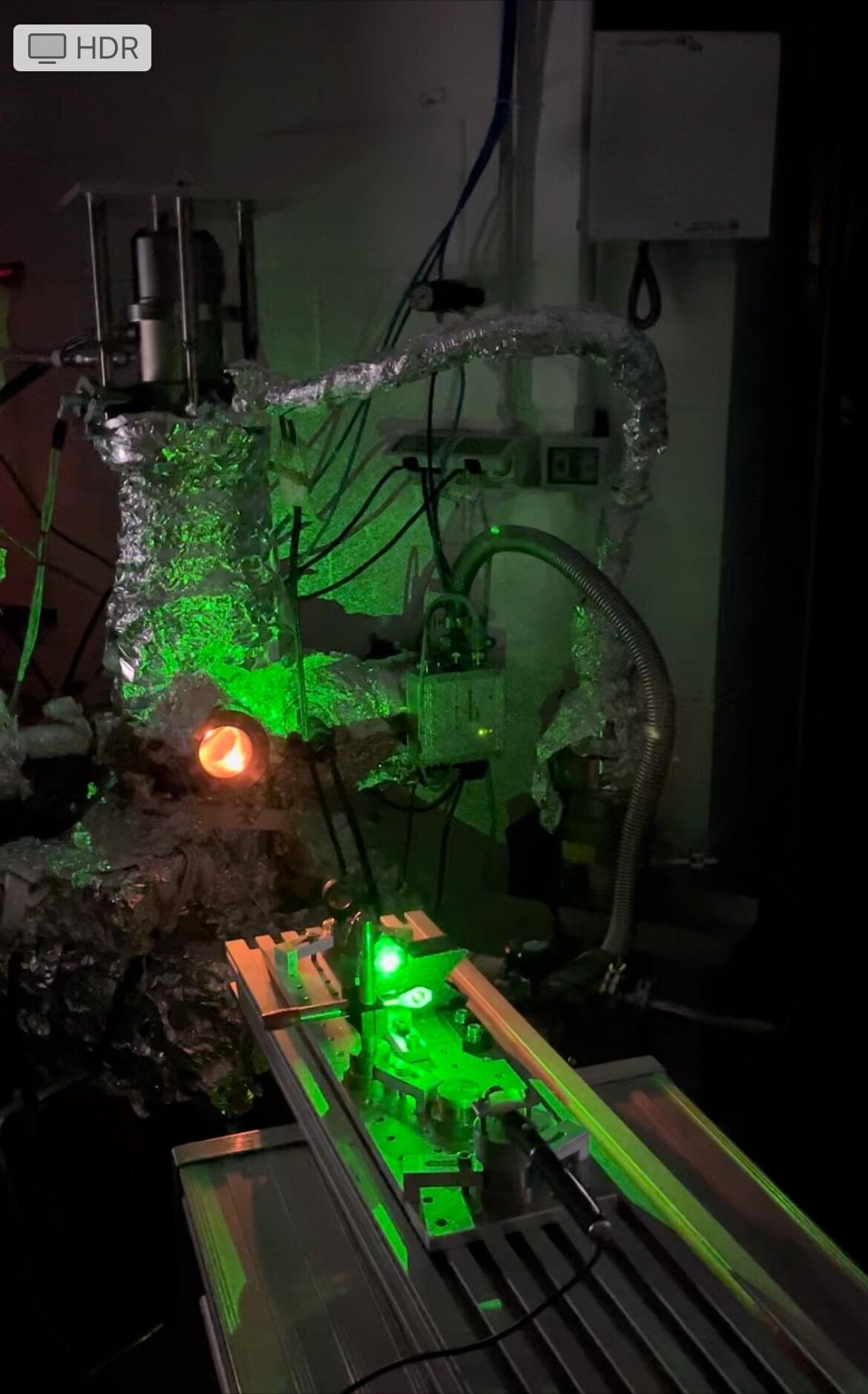

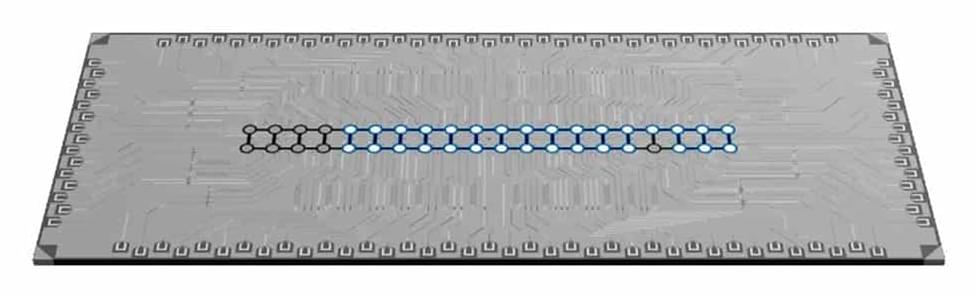

Researchers at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics and Munich Center for Quantum Science and Technology (MCQST) recently realized a strongly interacting phase of matter in large-scale bosonic flux ladders, known as the Mott-Meissner phase, using a neutral atom quantum simulator. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, could open new exciting possibilities for the in-depth study of topological quantum matter.

“Our work was inspired by a long-standing effort across the field of neutral atom quantum simulation to study strongly interacting phases of matter in the presence of magnetic fields,” Alexander Impertro, first author of the paper, told Phys.org. “The interplay of these two ingredients can create a variety of quantum many-body phases with exotic properties.