The discovery of pyrene in this far-off cloud, which is similar to the collection of dust…

A team led by researchers at MIT has discovered that a distant interstellar cloud contains an abundance of pyrene, a type of large, carbon-containing molecule known as a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH).

The discovery of pyrene in this far-off cloud, which is similar to the collection of dust and gas that eventually became our own solar system, suggests that pyrene may have been the source of much of the carbon in our solar system. That hypothesis is also supported by a recent finding that samples returned from the near-Earth asteroid Ryugu contain large quantities of pyrene.

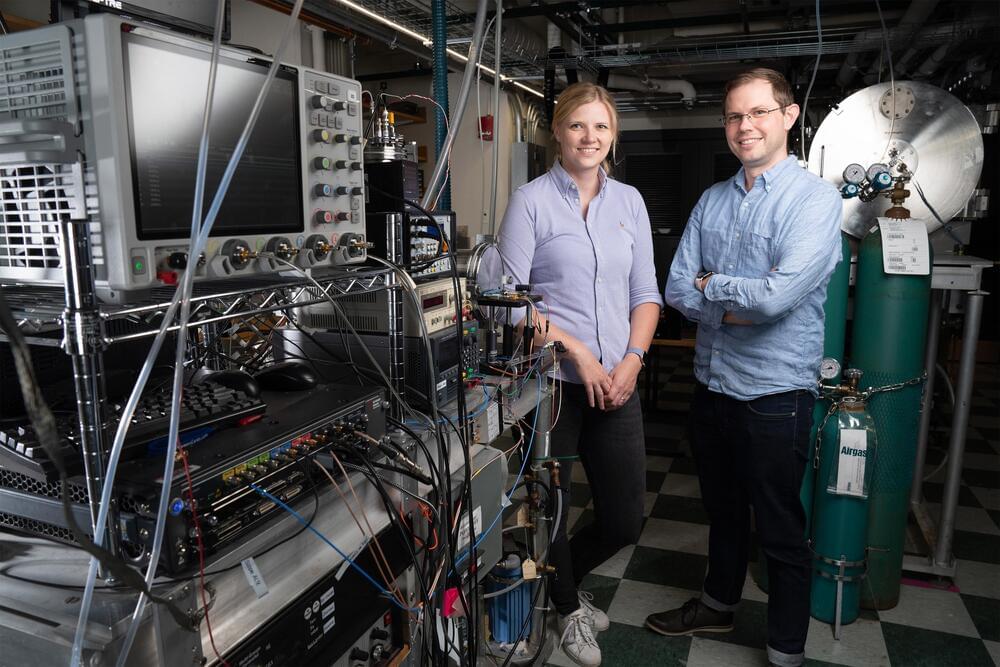

“One of the big questions in star and planet formation is: How much of the chemical inventory from that early molecular cloud is inherited and forms the base components of the solar system? What we’re looking at is the start and the end, and they’re showing the same thing. That’s pretty strong evidence that this material from the early molecular cloud finds its way into the ice, dust, and rocky bodies that make up our solar system,” says Brett McGuire, an assistant professor of chemistry at MIT.