Researchers at the UPC’s Department of Electronic Engineering have developed a new type of magnetometer that can be integrated into microelectronic chips and that is fully compatible with the current integrated circuits. Of great interest for the miniaturization of electronic systems and sensors, the study has been recently published in Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) are electromechanical systems miniaturized to the maximum, so much so that they can be integrated into a chip. They are found in most of our day-to-day devices, such as computers, car braking systems and mobile phones. Integrating them into electronic systems has clear advantages in terms of size, cost, speed and energy efficiency. But developing them is expensive, and their performance is often compromised by incompatibilities with other electronic systems within a device.

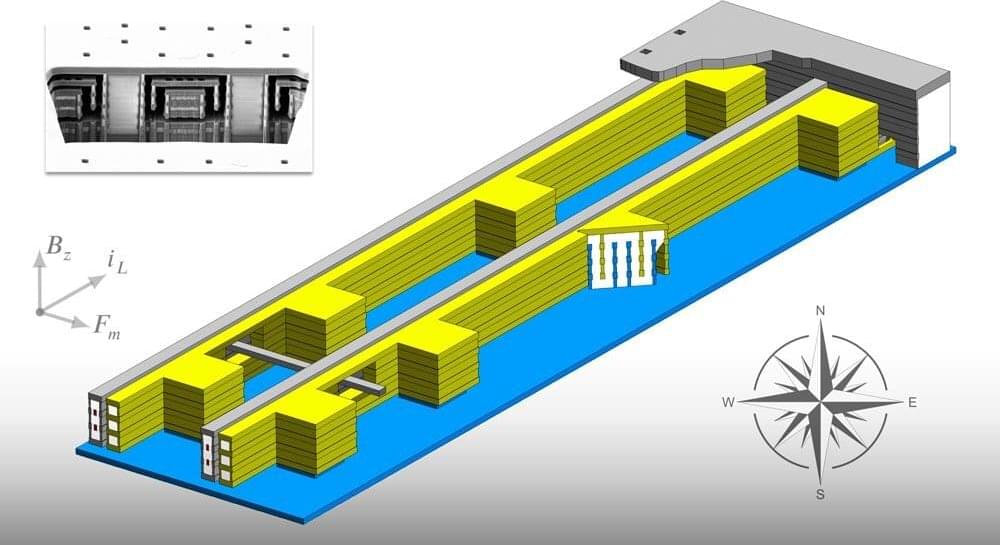

MEMS can be used, among many others, to develop magnetometers—a device that measures magnetic field to provide direction during navigation, much like a compass—for integration into smartphones and wearables or for use in the automotive industry. Therefore, one of the most promising lines of work are Lorentz force MEMS magnetometers.