The search space for protein engineering grows exponentially with complexity. A protein of just 100 amino acids has 20100 possible variants—more combinations than atoms in the observable universe. Traditional engineering methods might test hundreds of variants but limit exploration to narrow regions of the sequence space. Recent machine learning approaches enable broader searches through computational screening. However, these approaches still require tens of thousands of measurements, or 5–10 iterative rounds.

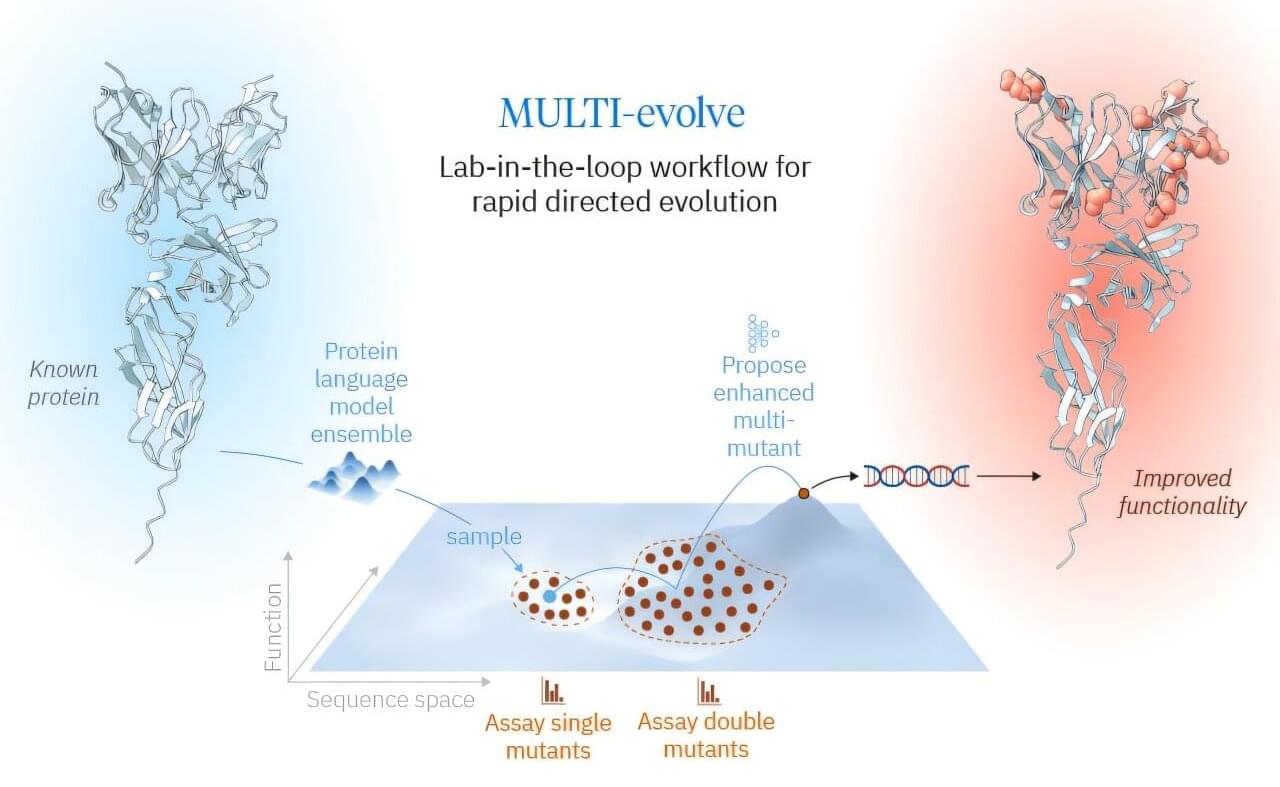

With the advent of these foundational protein models, the bottleneck for protein engineering swings back to the lab. For a single protein engineering campaign, researchers can only efficiently build and test hundreds of variants. What is the best way to choose those hundreds to most effectively uncover an evolved protein with substantially increased function? To address this problem, researchers have developed MULTI-evolve, a framework for efficient protein evolution that applies machine learning models trained on datasets of ~200 variants focused specifically on pairs of function-enhancing mutations.

Published in Science, this work represents Arc Institute’s first lab-in-the-loop framework for biological design, where computational prediction and experimental design are tightly integrated from the outset, reflecting a broader investment in AI-guided research.